The Intersection of Public Health and Direct Patient Care: What Pediatricians Should Know

AUTHORS:

Matthew Fifolt1, Lisa C. McCormick2, Leslie M. Beitsch3, and Paul C. Erwin1,4

1Department of Health Policy and Organization, University of Alabama at Birmingham

2School of Public Health and Department of Environmental Health Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham

3Department of Behavioral Sciences and Social Medicine, Florida State University College of Medicine

4School of Public Health and Department of Health Policy and Organization, University of Alabama at Birmingham

review article | PUBLISHED Winter 2024 | Volume 44, Issue 1

DOWNLOAD PDF

Even as the United States and the world continue to count the devastating costs of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) outbreak in terms of human lives and financial resources, the pandemic has shed light on the need for a robust public health system to prevent the spread of infectious and communicable diseases.1 After years of an overall divestment in the U.S. public health infrastructure and a trend towards reactionary funding to emergent crises,2 experts have suggested that increased awareness of funding and workforce needs due to the pandemic may reinvigorate the current public health enterprise.3 Nevertheless, interest in public health has already started to wane as individuals perceive the immediate crisis to be over.4 Even among those who might benefit the most from greater knowledge of public health programs and services (i.e., physicians), priorities have begun to shift to concerns exacerbated by the pandemic (e.g., behavioral health, well-child visits, vaccinations, health equity).5 Therefore, it is incumbent upon the profession to fully articulate how public health safeguards population health.

This article aims to provide a high-level overview of public health, including areas of focus, key functions, and strategic services. This topic may interest the general public, but we have written it for physicians as our primary audience, specifically pediatricians in Florida. The following three questions serve as our major headings for the article:

- What is Public Health?

- With which Public Health programs and services should pediatricians be most familiar?

- How can pediatricians and health departments work together to support public health?

What is Public Health?

Fundamentally, public health involves society’s collective efforts to (1) prevent disease, (2) prolong life, and (3) promote health. Researchers have used the upstream/downstream metaphor to describe how public health actions, policies, and interventions focus on macro-level (upstream) factors to address individual health (downstream) concerns.6,7 For example, an upstream public health initiative might include adding parks, walkways, and green spaces to residential areas to increase physical activity among residents. This is just one illustration of how public health strives to address the social determinants of health or nonmedical factors influencing health outcomes.8 To further exemplify how public health protects and improves health, we describe the three core functions and ten essential public health services that comprise a framework for carrying out the public health mission.9

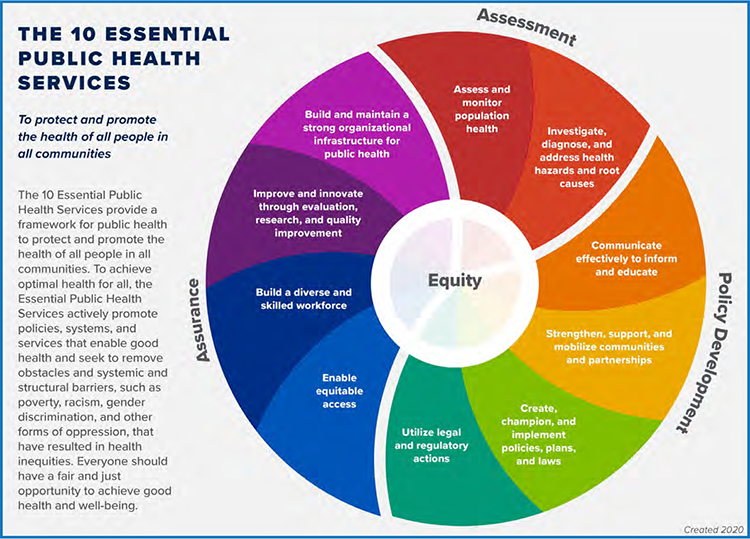

Figure 1: Essential Public Health Services Framework

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

Three Core Functions and 10 Essential Public Health Services

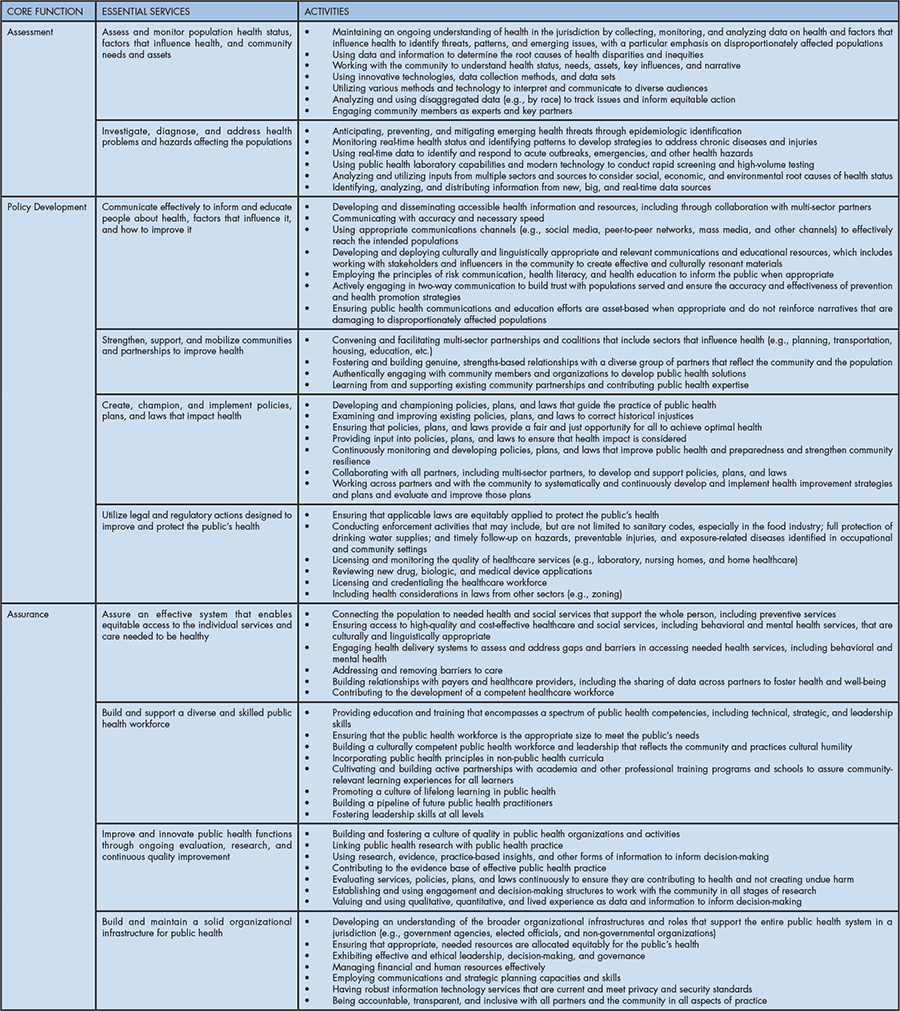

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the three core functions of public health, assessment, policy development, and assurance, comprise ten essential public health services (EPHS). While the core functions are divided into essential services, the circular design of the framework suggests that there is no singular starting point for activation. Moreover, services across core functions may readily build upon one another. For additional information regarding the composition of the EPHS framework, including the three core functions and ten essential services and associated activities, see Table 1.

Table 1: Functional Depiction of the Essential Public Health Services Framework

The EPHS framework was developed in 1994 and updated in 2020 to better reflect current and future practice. Furthermore, discussions focused on how the EPHS could be used to create communities where people can achieve their best possible health.10 According to the authors, the updated EPHS framework was long overdue since the realities of the world over the previous 25 years had outpaced the original framework. The most compelling change to the EPHS is its central focus on equity, as depicted in the inner circle of the model and reflected in language changes throughout each of the ten services. According to Sellers et al., “Centering equity means that all public health work must reach towards two aims simultaneously: improving overall health and advancing equity.”11

Delivery of Public Health in the United States

The governmental public health system in the United States comprises public health agencies from the federal government (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), 50 states plus the District of Columbia, local governments, and federally recognized tribal and territorial agencies.12 Due to this complex network of people and organizations, the public health infrastructure in the United States is highly diverse. As described by Mays et al., “Some [state and local public health] agencies operate as freestanding, independent departments, whereas others are embedded within larger ‘super agency’ structures that have responsibilities for an array of health and social service programs.”13

The governmental authority for public health derives from the 10th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states that any powers not “delegated to the United States by the Constitution nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”14 This is the basis of federalism. Public health powers are then described as a subset of the police powers established under the 10th Amendment, further elaborated at the state and local levels. Thus, the major locus of public health authority in the United States is at the state level; whatever authorities are then delegated to local government is a matter of each state’s constitution and statutes. In Florida, authority is granted through state statute.

The structure of local health departments varies, but they all share the common goal of promoting and protecting community health. Nevertheless, differences in structure have important implications for delivering essential public health services. Moreover, public health authority’s roles, responsibilities, and scope rely on state policy and the government’s relationship between state and local health departments.15 Florida has a centralized structure in which all local health departments are units of state government.16

State Health Departments

State health departments provide population-based health services related to primary prevention, screening, and treatment of diseases and conditions. Typical duties of a state health department include (1) disease surveillance, epidemiology, and data collection; (2) state laboratory services; (3) preparedness and response to public health emergencies; (4) population-based primary prevention; (5) health care services; (6) regulation of health care providers and other licensed professions; (7) environmental health; and (8) technical assistance and training.17 The state of Florida fits within this national framework.

Local Health Departments

In 2019, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) concluded that most local health departments (70%) are locally governed. The remaining 30% were either units of the state health agency or had a shared governance structure.18 Functions of local health departments vary but may include oversight (i.e., responsibility for public health performance), policy development, legal authority, continuous quality improvement, resource stewardship, and partner engagement. Local health departments range in size from one employee (e.g., agencies in Massachusetts that have a local health department in all 351 towns and cities) to over 4,000 employees (e.g., Los Angeles County Health Department).

Structure of County Health System in Florida

As noted above, Florida’s public health system is an example of a centralized state health department structure, where the state maintains direct authority over all 67 county health departments. At the state level, the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) is an executive branch agency led by the State Surgeon General, who also serves as the State Health Officer (SHO)/Secretary of Health and is directly appointed by Florida’s Governor and confirmed by Florida’s Senate.19 In addition to the state health office in Tallahassee and Florida’s 67 County Health Departments (CHDs), the FDOH includes 12 Medical Quality Assurance (MQA) regional offices, nine Disability Determinations regional offices, and three public health laboratories.19 Four Deputy Secretaries for Health manage the various programs and services of the FDOH, including the Deputy Secretary for Children’s Medical Services (who controls all CMS Offices); the Deputy Secretary for Health (over vital statistics, emergency preparedness, community health promotion, and disease control and health protection); the Deputy Secretary for Operations (over finance and accounting, regulation and licensure, executive boards, and disability determinations); and the Deputy Secretary for County Health Systems (over the 67 CHD offices).

The directors of those CHDs are appointed by and report to the Deputy Secretary for County Health Systems after the concurrence of the board of county commissioners of the respective county.20 The various CHD facilities and offices are provided through partnerships with local county governments and owned by the counties even if constructed with state funds. In addition to the main CHD office in each county, 188 affiliated sites throughout the state provide an array of public health services, ranging from a single service (e.g., an office for providing the special supplemental nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC]), to large sites that provide multiple programs and services. Funding for CHDs comes from a mix of local, state, and direct federal sources and fees for services rendered. Historically, statewide, the percentage of funding from these sources has been approximately 10% local, 50% state and federal, and 20% Medicaid and Medicare, with the remaining 20% from various other sources, including fees.

Services and programs provided by CHDs differ across the state, depending on local resources and other local services availability, the size of the county, and specific needs. A complete listing of programs and services can be found at https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/index.html. Florida State Statutes21 describe three general groups of services that are most commonly provided:

- “Environmental health services,” including food hygiene, safe drinking water supply, sewage, and solid waste disposal, swimming pools, group care facilities, migrant labor camps, toxic material control, radiological health, occupational health, and entomology.

- “Communicable disease control services,” including epidemiology, sexually transmissible disease detection and control, immunization, tuberculosis control, and maintenance of vital statistics.

- “Primary care services,” including first contact acute care services; chronic disease detection and treatment; maternal and child health services; family planning; nutrition; school health; supplemental food assistance for women, infants, and children; home health; and dental services.

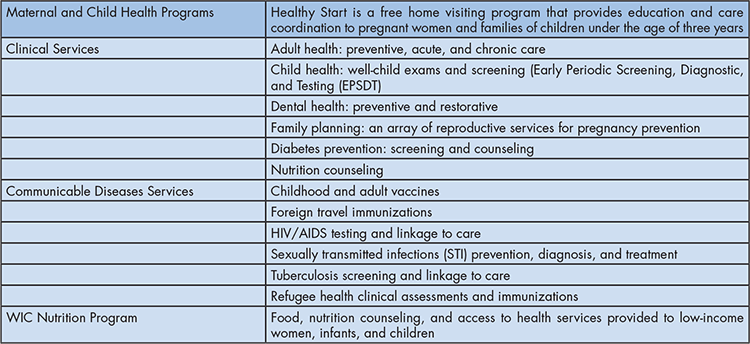

From a more programmatic perspective, these statutes translate into a set of core public health services and programs common for almost all CHDs (see Table 2).

Table 2: Core Public Health Services and Programs

County health departments also provide access to birth and death certificates, community health programs such as SNAP-ed (nutrition education for families), and the Florida Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. County health departments oversee the School Health Services Program, providing school health nurses in public schools across the state. Services range from basic to comprehensive to full, based on funding availability.22 (For a complete description of these different levels of school health services, see https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/childrens-health/school-health/school-health-program.html).

Basic school health services include health appraisals; nursing assessments; child-specific training; preventive dental screenings and services; vision, hearing, scoliosis, and growth and development screenings; health counseling; referral and follow-up of suspected or confirmed health problems; first aid and emergency health services; assistance with medication administration; and health care procedures for students with chronic or acute health conditions.22 Separate from CHDs but under the auspices of the FDOH, the Children’s Medical Services System provides an array of programs that serve children with special health care needs (CSHCN) through 22 area offices. These services use statewide networks of specially qualified doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals that provide care to children with special needs. This program is closely coordinated with the state Medicaid program and is among the largest networks for CSHCN in the nation.

While CHDs are under the direct authority of FDOH, they must also be responsive to their county government through their County Commission. County health department budgets must be approved by both the County Commission and the State Health Office, and Florida law requires County Commission concurrence with the appointment of the county health officer or county administrator. Historically, CHDs in Florida have not been governed by county Boards of Health, with a few exceptions.

Accreditation of State and Local Health Departments in Florida

State and local health departments are accredited by the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB), a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the continuous quality improvement (CQI) of tribal, state, local, and territorial public health departments.23 In 2016, FDOH received first-in-the-nation national accreditation as an integrated department of health through PHAB.24 This distinction signified that FDOH, including the state office and all 67 county health departments, had been “rigorously examined and meets or exceeds national standards for public health performance and continuous quality improvement.”24 In a recent press release by the Florida News, FDOH announced its reaccreditation as an integrated system by PHAB for the next five years.24 State Surgeon General Ladapo stated, “Working to continually improve the quality and performance of our services allows the department to keep communities ahead of emerging health threats and ongoing health challenges.”25

With which Public Health programs and services should pediatricians be most familiar?

The following public health services and programs are the most relevant for pediatricians who practice in Florida, especially those in private practice settings.

- Immunizations

Providing childhood vaccines remains one of the most frequent reasons for visits to the pediatrician, and in Florida, there are two main options FDOH provides to support vaccinating children. First, a pediatrician may enroll in the federally-funded Vaccines for Children (VFC) program managed by FDOH, which provides vaccines to Medicaid-eligible children and VFC Program-eligible children who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid. The VFC Program enrolls both Medicaid and non-Medicaid providers, who then provide immunizations to VFC Program-eligible children.26 Vaccines are shipped directly to the pediatrician’s office at no cost. Pediatricians may bill Medicaid for office visits and vaccine administration fees; VFC-eligible families not covered by Medicaid or Medicaid HMOs may be charged a vaccine administration fee. If a patient has no insurance and receives an immunization through Florida Shots, they can be billed for the administration fee. However, only one bill can be sent, and bills cannot be sent to collections. By rule, providers may not refuse administering a vaccine to a VFC-eligible child due to an accompanying adult’s inability to pay an administration fee.27 A second option available to the pediatrician is to refer VFC-eligible children directly to the nearest CHD, where they may receive the necessary vaccinations.

- WIC and nutrition counseling

The special supplemental food program known as WIC is a nutrition-centered program for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding or who have recently been pregnant, and infants and children under age five years.28 The WIC program provides not only financial support for the purchase of healthy foods but nutrition education, counseling, and breastfeeding support. Eligibility guidelines for WIC include all children enrolled in Medicaid and non-enrolled families who meet specific income criteria. Children may be determined to be “at risk” by being either underweight or overweight and receive nutrition counseling services from nutritionists at the CHD. This is one of the few options available for low-income families to receive counseling for children who are overweight. Breastfeeding support services vary by county, depending on the availability of a Certified Lactation Counselor; CHDs may also have a breastfeeding peer counseling program.

- Children’s Medical Services (CMS)

Children with special medical needs, including those with complicated, chronic, multi-system conditions may be referred to CMS to determine eligibility for clinical and supportive services. There are both general and clinical eligibility requirements. Typically, children with special health care needs younger than 21 years of age who have chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and who also require health care and related services of a type or amount beyond that which children generally require will qualify for CMS. Over the past decade, the CMS system has transitioned from regional offices providing care and wrap-around services to a statewide managed care organization as the service provider. Since 2021, Sunshine Health has been a managed care organization. Over 90,000 children are currently enrolled. Presently, Sunshine Health is jointly overseen by FDOH (CMS) and the Agency for Health Care Administration, which is responsible for the state Medicaid program. The general eligibility groups for CMS include the following:

- Medicaid eligible (Title XIX)

- Florida KidCare SCHIP (Title XXI)

- Children with Special Health Care Needs with family incomes over 200% FPL with spend-down to Medicaid levels

- High-risk pregnant females eligible for Medicaid

Clinical eligibility focuses more on medical conditions and includes medical, behavioral, or developmental conditions that have lasted or are expected to last at least 12 months. For example, these congenital, genetic, chronic, or catastrophic conditions are representative of those covered by CMS:

- ADD/ADHD

- Brain and Spinal Cord Injuries

- Cancer

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Diabetes

- Hemophilia

- Sickle Cell Anemia

- Spina Bifida

The benefits of CMS program services span the full range of care, including prevention and early intervention services, primary and specialty care, and long-term care for medically complex, fragile children. Families may receive other services that are medically necessary, such as respite care, genetic testing, genetic and nutritional counseling, and parent support.29

CMS also has other roles and services. It is the agency responsible for Florida’s infant metabolic screening program for early recognition of genetic disorders. The infant hearing screening program was among the first to be established in the nation. Additionally, CMS oversees the Poison Control Center network. Child Protection Teams operate statewide in close collaboration with the Department of Children and Families to detect children suffering from abuse and neglect. Early Steps, Florida’s early intervention program, is another important program under the CMS umbrella.

- Other services for infants, children, and adolescents

In addition to the three program areas detailed above, the following list includes other FDOH services of which pediatricians should be aware:

- Lead poisoning/testing: https://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/lead-poisoning/parent-info.html

- Safe Kids Florida, which includes the provision of car seats: https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/safe-kids-florida/index.html

- Family planning, including services for teens: https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/womens-health/family-planning/index.html

- Sexually transmitted infections screening, diagnosis, and treatment: https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/sexually-transmitted-diseases/index.html

How can pediatricians and health departments work together to support public health?

State and local health department representatives play an essential role in educating lawmakers about the needs of their communities; however, as governmental health employees, public health officials cannot advocate or lobby elected officials on behalf of public health programs and policies. Notwithstanding these limitations, advocacy for public health programs, policies, and positions is critical to maintaining the mission of public health to “fulfill society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy.”30 Therefore, governmental public health frequently relies on other entities to advocate for local and state policies that protect and improve the health of all people and their communities.31 One critical partner for local and state public health departments is the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

American Academy of Pediatrics

Historically, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has been one of the most important organizations for ensuring the public’s health. This member organization of 67,000 pediatricians is committed to “the optimal physical, mental, and social health and well-being for all infants, children, adolescents, and young adults.”32 Since its founding in 1930, the AAP has served as a unified voice for collective action through policy, advocacy, and education. In addition to the national organization, AAP has 59 chapters in the United States and seven in Canada. The Florida Chapter of the AAP (FCAAP) comprises 2,500 members, and its advocacy efforts help shape the laws and policies that govern the delivery of children’s healthcare services in Florida.33

Advocacy Programs and Policies

As an example of Florida-specific advocacy on the part of pediatricians, the following section describes policy statements and advocacy efforts by AAP and others to protect individuals from tobacco, including the hazards of secondhand smoke and an innovative program designed to empower youth to work towards a tobacco-free future. Additionally, we identify two emergent public health crises that will require an all-hands-on-deck approach to protect the public’s health: vaccine hesitancy and gun safety.

Tobacco

The Florida Clean Air Act (FCIAA) was enacted in 1985 by the Florida Legislature to protect people from the health hazards of secondhand smoke. In 2003, the legislature passed a voter-approved amendment to prohibit smoking in workplaces that previously allowed smoking. In 2019, electronic vapor products were included in the FCIAA and, therefore, prohibited in indoor workplaces.34 AAP has continuously advocated for greater restrictions on the use of tobacco products in all indoor and outdoor public places.

According to an AAP Issue Brief, “Not only are children more likely to suffer health consequences from exposure to secondhand smoke, but adolescents are the age group most susceptible to becoming addicted to tobacco products.”35 Therefore, AAP recommends that pediatricians should counsel parents about the importance of maintaining tobacco-free environments for children, including homes, cars, schools, childcare programs, playgrounds, and other venues. Furthermore, at the individual level, the AAP encourages pediatricians to seek appointment to the state tobacco advisory committee to advise the Surgeon General on the direction and scope of the Comprehensive Statewide Tobacco Education and Use Prevention Program as outlined in the state constitution. In Florida, the Tobacco Advisory Council meets quarterly to recommend policies to encourage a coordinated response to tobacco use in the state.36 Additionally, FCAAP convenes issue-oriented task forces to effect real change around the most pressing pediatric health challenges facing Florida’s children, including an e-cigarette task force to promote health policies and best practices on vaping and support curbing the vaping epidemic in the pediatric population.37

Students Working Against Tobacco (SWAT)

In 1997, the State of Florida settled a lawsuit against tobacco companies; the late Governor Lawton Chiles directed settlement monies to fund a state program to prevent youth smoking.38 In 1998, Florida established Students Working Against Tobacco (SWAT), a youth-led program to “develop a coordinated, unified assault against the manipulation of Big Tobacco… (through) tobacco prevention activities.”39 Under the guidance of FDOH, SWAT has become an important part of the political process in Florida, educating key decision-makers about the necessity of tobacco prevention. SWAT chapters exist in all 67 counties in Florida and are divided into one of five regions. Pediatricians can connect with the Regional Tobacco Prevention Coordinator in their region by visiting:

- http://www.gen-swat.com/gen-swat1/contact.html

Vaccine Hesitancy

AAP remains a steadfast champion of preventive care, including immunizations, as a major component of pediatric health care and disease prevention. Therefore, advocacy efforts by AAP focus on educating the public and key decision-makers about the importance of routine child immunization and actively countering misinformation about vaccine safety and efficacy.40 However, as stated by Olson and colleagues, “Parental vaccine hesitancy is becoming an increasingly important public health concern in the United States.”41 According to the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), vaccine hesitancy refers to “[d]elay in the acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place, and vaccines. It is influenced by factors like complacency, convenience, and confidence.”42

Despite overwhelming evidence of the effectiveness and safety of vaccinations, parental vaccine hesitancy is prevalent in the United States.43 These concerns have only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Results of a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) suggest that many parents are adopting a wait-and-see approach before vaccinating their child, and approximately 30% said they would “definitely not” get their child under five years of age vaccinated for COVID-19. Parents’ primary apprehensions were related to unknown long-term effects and serious side effects of the vaccine, including concerns that the vaccine may affect their child’s future fertility despite the absence of evidence of such an effect.44

As reported by Messerly and Mahr, one of the biggest fears among public health experts, pediatricians, immunization advocates, and state officials is that “an increasing number of families are projecting their attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine onto shots for measles, chickenpox, meningitis and other diseases.”45 Additionally, concerns have been raised regarding state legislatures either removing or limiting school vaccination requirements, which may lead to greater vaccine hesitancy among parents of school-age children. Based on the results of a nationally representative survey, Hammershaimb and colleagues stated that efforts to ensure COVID-19 vaccine uptake should include messaging to increase overall confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine among U.S. adults.46 Belief in the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination and acceptance of routine childhood vaccines were the strongest predictors of parents’ intention to vaccinate their children.

Eller and colleagues suggested that providers can be key in encouraging parents to follow the recommended vaccine schedule.47 The researchers noted that while most parents trusted their child’s doctor for vaccine information, mothers who had less trust in their health providers more frequently reported using more informal and potentially less reliable sources of vaccine information (e.g., internet, family and friends, media other than internet). Therefore, it is imperative that pediatricians maintain trusting relationships with patients to ensure compliance with the recommended vaccine schedule and to minimize conflicting reports and suggestions from less dependable data sources.

In a recent press release, FCAAP President Lisa Gwynn stated, “FCAAP and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) are dedicated to protecting Florida’s children and will continue to urge Gov. DeSantis to allow parents who choose to do so the option to vaccinate their young children against COVID-19.”48 Moreover, FCAAP affirmed that COVID-19 vaccines for children are “safe, effective, and the best available tool to prevent serious illness.”48 Unfortunately, that press release resulted in the removal of Dr. Gwynn from the board of directors of the Florida Healthy Kids Corporation, as her statements were viewed as “very political” by Florida’s chief financial officer.49 This action demonstrated that advocacy, even when supported by science, can still carry political risk but is required for advancing crucial public health policies and programs.

Gun Violence

According to the Pew Research Center, more than 45,000 people died from gun-related injuries in the United States in 2020, the most recent year for which complete data are available. This number represents a 14% increase from 2019 and a 43% increase from 2010, and it includes suicides (54%), murder (43%), and other (3%), such as unintentional, involved law enforcement, or undetermined circumstances.50 Moreover, in 2020, gun violence overtook motor vehicle accidents to become the number one cause of death for U.S. children and adolescents.51

In a recent report issued by The Trace, the authors noted a dramatic rise in youth suicide, with the sharpest increases among people of color. Between 2011 and 2020, “The firearm suicide rate more than doubled among Black, Latino, and Asian teenagers, while it increased by 88 percent for Native Americans and 35 percent for white teens.”52 Findings from a qualitative study of factors associated with childhood suicide (children aged 5 to 11) revealed that firearms were the second most prevalent method of suicide, behind hanging or suffocation, and among all cases with detailed information, all of the children/adolescents who completed suicide with guns used guns that had been stored in an unsafe manner.53

The Florida Medical Association was an early supporter of counseling patients on the safe storage of guns in the home. Similarly, the AAP has been a longtime advocate for meaningful policy change to keep children safe from guns. In a recent AAP press release, Dr. Lee, incoming chair of the AAP Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, stated:

We as a country need to take a public health approach that mixes safe storage of guns at home to keep them out of the hands of children and teenagers and common-sense legislative approaches that reduce the incidence and impact of community violence.54

Based on the advocacy efforts of the AAP and other physician, nurse, and hospital groups, President Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act into law at the end of June 2022. This legislation includes measures to limit access to guns among young adults, individuals who have committed acts of domestic violence, and individuals who are considered a danger to themselves or society.55 According to the AAP president, this bill also includes “funding to expand mental health services for children and adolescents in communities and schools, and funds and reauthorizes the AAP-championed Pediatric Mental Health Care Access program,” which supports pediatricians with telehealth consultation by child mental health provider teams.56

The AAP recommends that pediatricians address firearm safety as part of routine care for families with children of all ages. The AAP offers pediatricians training and resources that help them have productive conversations about how best to store firearms to protect children and young people. One resource available to pediatricians is the AAP Gun Safety Campaign Toolkit, available here:

- https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/campaigns-and-toolkits/gun-safety/

Florida pediatricians can assume a leadership role on the topics of gun violence and gun safety through FCAAP’s gun violence task force, whose mission is to educate pediatricians and the community on the risks and dangers of gun violence and provide resources regarding gun safety education and training, mental health resources, and reasonable legislative measures to curb the safety risks to children and families.37

Conclusion

Public health and pediatricians are natural allies–both focus on infant, child, and adolescent health and well-being, strongly emphasizing primary prevention (i.e., vaccinations). For the practicing pediatrician, knowledge of the resources and services available through FDOH’s county health departments and other offices–especially CMS–can amplify and extend the care provided in the private practice office. If readers of this article react by saying (of FDOH), “I didn’t know they offered that,” then the article will have achieved its purpose. Pediatricians can have a direct voice in health department activities–as any citizen can–by attending County Commission meetings when the health department budget is being presented or when there is a new appointment of an administrator or health officer. However, pediatricians are especially well-positioned, through the FCAAP, to advocate for evidence-based interventions and community-based programs that protect the public’s health, as the examples on tobacco, vaccine hesitancy, and gun violence prevention demonstrate.

Understanding the structure of the local health department, how public health programs and services can best meet the needs of children and families, and how pediatricians can partner with their county health department empowers pediatricians to make full use of available resources. Moreover, fully participating in organizations like FCAAP to advocate for needed public health policies, programs, and funding strengthens the overall health system and ensures access to services to the most vulnerable populations in Florida.

References

- Benzkofer S. Pandemic shows need to overhaul public health system, experts say. November 3, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2021/11/pandemic-puzzle.html

- Maani N, Galea S. COVID-19 and underinvestment in the public health infrastructure of the United States. Millbank Q. 2020;98. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/covid-19-and-underinvestment-in-the-public-health-infrastructure-of-the-united-states/

- Johnson SR. ‘Provisional positives’: how the pandemic could spark a public health overhaul. January 6, 2022. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2022-01-06/how-the-covid-pandemic-could-spark-a-public-health-overhaul

- Gramlich J. Two years into the pandemic, Americans inch closer to a new normal. March 3, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/2022/03/03/two-years-into-the-pandemic-americans-inch-closer-to-a-new-normal/

- McMorrow S, Gonzalez D, Alvarez-Caravero C, et al. Urgent action needed to address unmet health care needs during the pandemic. October 2020. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103090/urgent-action-needed-to-meet-childrens-unmet-health-care-needs_0.pdf

- Freudenberg N, Franzosa E, Chisholm J, et al. New approaches for moving upstream: how state and local health departments can transform practice to reduce health inequalities. Health Educ. Behav. 2015;42(1 Suppl.):465-565.

- Ryan-Ibarra S, Hishimura H, Gallington K, et al. Time to modernize: local public health transitions to population-health interventions. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2021;27(5):464-472.

- Bharmal N, Derose KP, Felician M, et al. Understanding the upstream social determinants of health. May 2015. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1000/WR1096/RAND_WR1096.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 essential public health services. March 18, 2021. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html

- de Beaumont Foundation. 10 essential public health services. n.d. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://debeaumont.org/10-essential-services/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwmuiTBhDoARIsAPiv6L_9bHiys1RhVqluoOoLXXRKKHrcU23Ape-XWmdNmNiWNr52wyZu-2kaAuh_EALw_wcB

- Sellers K, Fisher JS, Kuehnert P, et al. Meet the revised 10 essential public health services: developed by the field, centering equity. March 25, 2021. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210319.479091

- Hyde JK, Shortell SM. The structure and organization of local and state public health agencies in the U.S.: a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;42(551):S29-S41.

- Mays GP, Smith SA, Ingram RC, et al. Public health delivery systems: evidence, uncertainty, and emerging research needs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009;36(3):256-265.

- Allan S. Legal basis of public health. In: Erwin P, Brownson R, ed. Scrutchfield and Keck’s Principals of Public Health Practice 4th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2016.

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). State public health agency classification: understanding the relationship between state and local public health. ASTHO and NORC at the University of Chicago; 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health department governance. November 13, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/sitesgovernance/index.html

- Beitsch LM, Brooks RG, Griggs M, et al. Structure and function of state public health agencies. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96(1):167-172.

- National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). National profile of local health departments. 2019. Accessed May 18, 2022. https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Programs/Public-Health-Infrastructure/NACCHO_2019_Profile_final.pdf

- Florida Department of Health. About us. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/about/

- Florida Department of Health. Florida Department of Health Organizational Chart. January 24, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/about/_documents/orgchart.pdf

- Florida Legislature. Title XI, Chapter 154: Public Health Facilities. 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0100-0199/0154/0154.html

- Florida Department of Health. School health program. Updated March 27, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/childrens-health/school-health/school-health-program.html

- Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB). About PHAB. 2022. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://phaboard.org/about/

- Florida Health. National accreditation. July 30, 2022. Accessed June 18, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/about/accreditation/index.html

- Florida Health. Florida Department of Health re-accredited by the Public Health Accreditation Board. March 15, 2022. Accessed June 18, 2022. https://darik.news/florida/florida-department-of-health-re-accredited-by-the-public-health-accreditation-board/202203547533.html

- Florida Department of Health. VFC program provider guidelines. Updated November 26, 2019. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/immunization/vaccines-for-children/vfc-program-guidelines/index.html

- Florida Department of Health. Vaccines for children (VFC) program policy handbook. 2021. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/immunization/vaccines-for-children/_documents/2021-vfc-provider-handbook.pdf

- Florida Department of Health. Women, infants, and children (WIC). Updated June 10, 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/wic/index.html

- Florida Department of Health. Children’s medical services program overview. Updated November 10, 2021. Accessed June 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/childrens-health/childrens-medical-services/index.html

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). The Future of Public Health. National Academy Press; 1988.

- CDC Foundation. Public health in action. 2022. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.cdcfoundation.org/what-public-health

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). About the AAP. 2022. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/about-the-aap/

- Florida Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (FCAAP). FCAAP. 2022. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.fcaap.org/

- Florida Health. Florida clean indoor act. June 16, 2022. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/prevention/tobacco-free-florida/indoor-air-act/index.html

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Issue brief. Tobacco-free environments. January 2012. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/Tobacco_freeEnvironments_IssueBrief.pdf?_ga=2.8258482.1626136998.1656355642-903705257.1656258394&_gac=1.196289246.1656259202.CjwKCAjwh-CVBhB8EiwAjFEPGYfF-igkjmTjSvMO9j7oQ-dzJ-p0iSwP08pe7cN6HuupTMIinuxFWRoCsvQQAvD_BwE

- Florida Health. Tobacco Advisory Counsel. June 16, 2022. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/prevention/tobacco-free-florida/tobacco-advisory-council.html

- Florida Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (FCAAP). FCAAP committees & task forces. 2022. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.fcaap.org/about-fcaap/committee/

- Archer M. Teens’ message to peers: No smoking. August 30, 1998. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-xpm-1998-08-31-9808310191-story.html

- SWAT. Get to know us. 2022. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://www.swatflorida.com/get-to-know-us/

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Childhood immunizations. 2022. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/state-advocacy/childhood-immunizations/

- Olson O, Berry C, Kumar N. Addressing parental vaccine hesitancy towards childhood vaccines in the United States: a systematic literature review of communication interventions and strategies. Vaccine. 2020;8(590). doi:10.3390/vaccines8040590

- World Health Organization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE). Report of the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. October 2014. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.asset-scienceinsociety.eu/sites/default/files/sage_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf

- Kempe A, Saville AW, Albertin C, et al. Parental history about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1): e20193852.

- Sparks G, Lunes L, Montero A, et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: April 2022. May 4, 2022. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-april-2022/

- Messerly M, Mahr K. Covid vaccine concerns are starting to spill over into routine immunizations. April 18, 2022. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/04/18/kids-are-behind-on-routine-immunizations-covid-vaccine-hesitancy-isnt-helping-00025503

- Hammershaimb EA, Cole LD, Liang Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among US parents: a nationally representative survey. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2022. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piac049

- Eller NM, Henrikson NB, Opel DJ. Vaccine information sources and parental trust in their child’s health care provider. Health Educ. Behav. 2019;46(3):445-453.

- Florida Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (FCAAP). Florida pediatricians urge state officials to order COVID-19 vaccines for children under 5. June 17, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.fcaap.org/posts/news/press-releases/florida-pediatricians-urge-state-officials-to-order-covid-19-vaccines-for-children-under-5/

- Boboltz S. Florida pediatrician axed from state board for pro-vaccine comments. July 2, 2022. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://sports.yahoo.com/florida-pediatrician-axed-state-board-211417105.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAHt5yQK-1cdM17IqDdO6XtKoYbbLcVfVX0qdWj7d5_FwGSPJ5N-4Cm2FKqYf4yjD2aqK-5tlSmMHvPDg3mmvETgvb2vbPBkWe-76lyHThp9_GFYZw496j7YYXJO-sOLH49_1EShZAY9CE4bPxARF4SSPr3rbpO2ldMOqE1d0-KCb

- Gramlich J. What the data says about gun deaths in the U.S. February 3, 2022. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/02/03/what-the-data-says-about-gun-deaths-in-the-u-s/

- Wamsley L. The U.S. is uniquely terrible at protecting children from gun violence. May 28, 2022. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/05/28/1101307932/texas-shooting-uvalde-gun-violence-children-teenagers

- Mascia J, Pierce O. Youth gun suicide is rising, particularly among children of color. February 24, 2022. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.thetrace.org/2022/02/firearm-suicide-rate-cdc-data-teen-mental-health-research/

- Ruch DA, Heck KM, Sheftall AH, et al. Characteristics and precipitating circumstances of suicide among children aged 5 to 11 years in the United States, 2013-2017. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(7):e2115683. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15683. Accessed July 1, 2022.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Firearms deaths spike almost 30% during pandemic; gun homicides rise 35% from 2019-20. June 2, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/firearm-deaths-spike-almost-30-during-pandemic-gun-homicides-rise-35-from-2019-20/

- S.2938. Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. June 25, 2022. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2938

- Szilagyi M. AAP statement on state legislation to address gun violence. June 22, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/aap-statement-on-senate-legislation-to-address-gun-violence/