The Clash of Culture and Medicine: is Chiari 1 a Curse?

AUTHORS:

Jhulianna Vivar, BS1,2; Florence Desrosiers, MD, MBA3; Giovanna Salome, PhD4;

Rebecca Plant, MD1,2

1University of South Florida, Tampa, FL

2Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL

3University of Washington, Seattle, WA

4Universite de Stasbourg, Faculte des sciences sociales, France

Student Article | PUBLISHED SUMMER 2022 | Volume 42, Issue 3

DOWNLOAD PDF

Abstract

We often see the intersection of culture with medicine in the foods our patients consume, their activities of daily life, and their interpretation of disease states. However, unless we listen to their cultural, foundational beliefs, we can miss key factors that affect their health and outcomes. In this report, we discuss a case of a black teenage female born in Port-au-Price, Haiti, diagnosed with Chiari type 1 malformation with associated severe hydrocephalus and cervical, thoracic, and lumbar syringomyelia and cultural implications. She presented to her outpatient pediatrician for her well child exam with a secondary complaint of left arm weakness for the last four to five weeks. Given her grossly abnormal physical exam, she was admitted for a full evaluation diagnosing a Chiari type 1 malformation with the above complications. She underwent venticuloperitoneal shunt placement and revision within a week and refused pain control other than acetaminophen after surgery. Of note, the patient’s mother passed away shortly after her birth from a suspected caesarian section operative wound infection. Interestingly, hydrocephalus is considered a curse in the Haitian culture and children born with hydrocephalus are often hidden from society. In her culture, the death of our patient’s mother followed by developing hydrocephalus later in life could be considered evidence of the curse. It is well documented that pain is under recognized and under treated within our minority patients, but the cultural implications from being a product of a “curse” is a more worrisome outcome. Thus, it is imperative for us to be knowledgeable of our patient’s views and beliefs to provide competent care.

Abbreviations: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), external ventricular drain (EVD)

Key Words: pediatric, hydrocephalus, Chiari 1, pain, culture, Haitian

Introduction

Chiari malformations consist of herniated rhomboencephalic structures (pons, medulla oblongata, and the cerebellum) through the foramen magnum and can be associated with obstructive hydrocephalus and syringomyelia. A Chiari type 1 malformation is when the cerebellar tonsils herniate through the fossa by at least 5mm and is the most frequently diagnosed type. Often diagnosed when asymptomatic by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for headaches or other reasons, Chiari type 1 is a relatively common occurrence.1 However, when symptoms such as headaches that worsen with Valsalva, weakness, and/or parasthesias are present, surgical correction may be necessary.2 Within occidental medicine (western or disease-focused), this diagnosis has little to no cultural implications. However, in Haitian culture, hydrocephalus can be viewed as a curse on a family. Sociocultural values and therapeutic beliefs are important to consider in the evaluation and management of the Haitian patient. According to the 2018 United States census, there are over a million Haitian Americans living in the United States, and to provide competent care, we must attempt to listen and understand their culture.

Clinical Summary

We present a 15-year-old black Haitian female with no known significant medical history who presents to clinic for her well child exam. She had concerns of weakness and decreased sensation in the left upper and lower extremities and left trunk for 4 to 5 weeks. Symptoms began with occasionally dropping her phone and with a sensation of heaviness. Later she developed difficulty gripping objects and fully extending her fingers. She had never experienced symptoms like this before and did not have blurry vision, eye pain, difficulty swallowing, headache, nausea, vomiting or weakness elsewhere. Of note, she was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and moved to the United States at the age of 11 years with her Aunt and Uncle. According to the Uncle, her mother died shortly after her birth from an infected caesarian section surgical site.

On exam, her head was consistently tilting towards the right side though her speech was normal. She had tenderness on palpation of the left forearm and digits. Additionally, her 3rd, 4th, and 5th digits were flexed at rest and extension caused pain. Strength in her left upper extremity was 3/5 distally and 5/5 proximally and her left lower extremity was near normal. In comparison, her right upper and lower extremities had 5/5 strength throughout. Sensation was intact yet subjectively decreased throughout the left arm and hand. Finger-nose testing was abnormal on the left arm with a tremor at extension and flexion back to nose. Most concerning, her tongue deviated to the right upon protrusion.

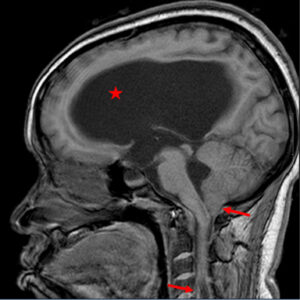

Upon further evaluation, her complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, serum magnesium, phosphorus, thyroid stimulating hormone, and serum creatine kinase were within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was slightly elevated at 31mm/hr [normal 0 – 20mm/hr]. MRI of the brain, cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine with and without contrast demonstrated severe ventriculomegaly with 8mm of tonsillar descent below the foramen magnum as well as a prominent cord syrinx spanning syrinx the entire cervical cord, medulla oblongata, and thoracic cord until T11-T12. (Figure 1). A diagnosis of Chiari 1 malformation with ventriculomegaly and syrinx was made.

Figure 1: T1 sagittal MRI with and without contrast. Star indicating significant obstructive hydrocephalus of the lateral ventricles, extending into the third and fourth ventricles. Left facing arrow indicating cerebellar tonsil extension through the foramen magnum. Right facing arrow indicating associated cervical cord syrinx.

Neurosurgery was performed two days after presentation with suboccipital decompression craniotomy with autologous duraplasty, C1 laminectomy, and right occipital external ventricular drain (EVD) placement. She tolerated the surgery well with no acute events. However, after five days in the pediatric intensive care unit there was minimal improvement in her weakness, sensation, and imaging, Neurosurgery proceeded with ventriculostomy and permanent ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement after which her ventricular caliber decreased slightly and her neurological exam improved including normal tongue protrusion. Her pain was well controlled by the intensivist during her sedated, immediate post-operative period. However, she requested minimal pain medication with only occasional acetaminophen despite two major surgeries. Prior to discharge home, merely ten days after initial presentation, she regained near normal strength in her left arm and left hand grip. A week after discharge, she was seen in clinic with near normal extremity strength, normal gait and coordination, and only mild pain at her surgical site.

Discussion

With the limitations of the Haitian medical system, preventive care is not fully integrated in Haitian customs., Haitians trust therapeutic resources that are less expensive and more familiar to them when they are sick. They use and trust traditional medicine (herbal tea and concoction), Houngans or Mambos (Vodou priest or priestess), Freemasons, or other spiritual healers. Diseases, and most importantly uncommon diseases, are seen as a curse sent by a jealous person or as a retribution for their family or their own actions. The majority of Haitians acknowledge a belief in those practices making occidental medicine the last step in their therapeutic process.3

For our patient, the mother’s death during childbirth is the first important clue in the history. This death might be considered a curse or retribution for what she had done in the past. Considering that the surviving child could carry the mother’s curse, traditional medicine with involvement of the Vodou priest or Houngan is usually the first step in addressing any physical or psychological ailment. Vodou Gods (also known as Loas) that are seen as guardians and protectors will receive supplication, and the Houngan will intercede on behalf of the family to help take out the curse. This process can take months and even years if there is no deterioration in the clinical presentation. Given the dearth of primary care and specialized medicine in Haiti and considering the trust of Haitians in traditional medicine, seeking medical care may be postponed and only occur if the patient is extremely ill.

Haitians, of course, carry their beliefs and sociocultural background with them upon arrival to the United States,. Although they may seek medical care sooner in the States than they would in Haiti, they withhold certain details of the medical history for fear of being misunderstood or for not being able to fully trust occidental medicine. As such, “Pluri-medicine” (jointly using occidental medicine and traditional Haitian medicine) is the norm rather the exception. All this background could explain our patient’s late presentation to care.

Another non-negligible cultural aspect for this patient is pain management. Growing up, a child is deemed “dur” (or resilient) on how the child handles different situations. Not verbalizing suffering, being strong, and avoiding complaining is culturally desired. Incessant complaining is considered shameful, but whether this learned behavior provides for a higher pain threshold remains to be proven. In general, it seems that the suffering exists but the shame one feels about complaining, the cultural tolerance of pain, and the resilience one must demonstrate are learned early in life. Asking for pain medication for everything is not a Haitian custom. It is most likely that our patient learned to cope with pain without complaining, or she may feel ashamed of not being able to sustain the pain that followed her surgery. This cultural attribute of avoidance to complaining could also attribute late presentation for care of her symptoms.

Overall, treating a Haitian patient while remaining sensitive to their background and being knowledgeable of their culture and beliefs creates a better alliance between the patient, family, and clinician and will ultimately improve the patient’s outcome. As a healthcare community, we must continue to educate ourselves on these cultural nuances to provide better care. By increasing awareness and cultural sensitivity, we can further earn our patient’s trust which ultimately enhances their care.

References

- Spazzapan P, Bosnjak R, Prestor B, Velnar T. Chiari malformations in children: An overview. World J Clin Cases. 2021 Feb 6;9(4):764-773. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.764. PMID: 33585622; PMCID: PMC7852648.

- McClugage, S. G., III, & Oakes, W. J. (2019). The Chiari I malformation, Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics PED, 24(3), 217-226. Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/24/3/article-p217.xml

- Desrosiers A, St Fleurose S. Treating Haitian patients: key cultural aspects. Am J Psychother. 2002;56(4):508-21. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.4.508. PMID: 12520887.