The ARCH Feedback and Guidance Model: Practical Strategies for Implementation

AUTHORS:

Dennis S. Baker, Ph.D.1

1Emeritus Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Rural Health, Florida State University College of Medicine

REVIEW ARTICLE | PUBLISHED Winter 2026 | Volume 46, Issue 1

DOWNLOAD PDF

Abstract

Overview/Introduction

The author conceptualized the ARCH Feedback and Guidance Model in 2003 at the Florida State University College of Medicine. It has been refined in partnership with Suzanne C. Bush, MD, and Gregory Turner, EdD.1 ARCH became an integral part of the medical school’s teaching methodology for clinical preceptors and remains so today. The ARCH model has been recognized and utilized by numerous medical schools, such as the Medical College of Wisconsin, Tufts University, Northeast Ohio Medical University, the University of Tampa, and the Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine. The Harvard-Macy Institute featured the ARCH Model in their January 2023 #MedEdPearls entitled, “The ARCH Guidance Model for Providing Effective Feedback.”2

The ARCH Feedback and Guidance Model aims to help learners become skilled at the habits associated with self-assessment and self-directed learning throughout the continuum of gaining knowledge and skills as medical students, medical residents, and independent physician health care providers. This article explains the ARCH model and strategies for how clinicians teaching students or residents in the office or hospital setting can utilize the model to enhance learners’ abilities to self-assess accurately and continuously develop strategies for self-directed learning.

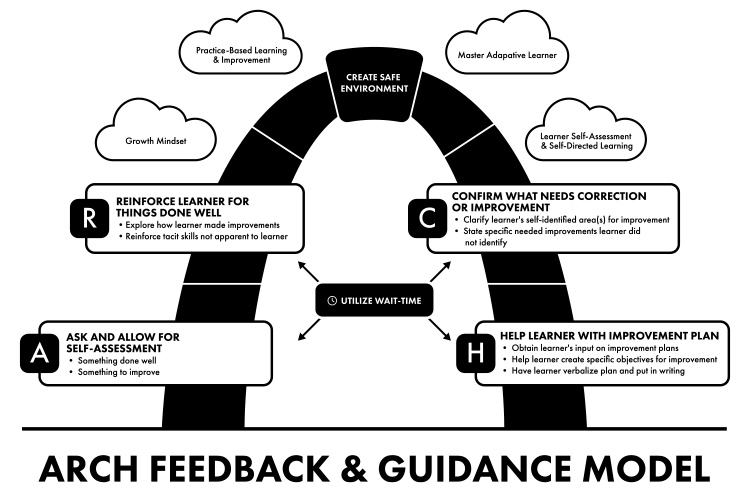

Four components constitute the structure of the ARCH model as follows:

A = Ask and Allow for Learner Self-Assessment

R = Reinforce Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Demonstrated by the Learner

C = Confirm with the Learner What Needs Correction or Improvement

H = Help the Learner with a Plan for Improvement

Each of these four components is described in this paper (See Figure).

Additional Feedback Models

Numerous feedback models are described in the medical education literature. Examples include: Pendleton’s Rules,3 Ask-Tell-Ask,4 R2C2,5 FEEDBK,6 and ADAPT.7

This paper does not describe these models, but references are provided for their accession. These models represent an effort to move beyond the infamous “Feedback Sandwich” and move to a feedback framework that engages the learner in a conversation with the teacher, purposed to help the learner create and implement strategies for improving knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

The primary purpose of these models is to help learners gain metacognitive skills to improve their performance continuously and with less dependency on others. The ARCH Feedback and Guidance model is an additional model for medical school faculty, residency faculty, and clinical preceptors to consider in efforts to enhance learners’ metacognitive skills and habits associated with self-directed learning.8

When and Where ARCH Can Be Implemented

This paper focuses on using ARCH in the clinical training setting (e.g., third- and fourth-year clerkships and throughout residency training). However, using ARCH in years one and two of medical school is also appropriate for the feedback and guidance processes associated with small group learning, simulation activities, objective structured clinical exams, etc. The advantage of the ARCH model is that it can be utilized throughout the continuum of medical education, including CME programming.

Wait-Time and ARCH

The ARCH model is an interaction between teacher and learner, driven by teacher questions and learner responses. When asking the learner a question, the instructor should give the learner a 3 to 5-second time-frame of silence to create and deliver a response. This 3 to 5 seconds of instructor silence after the instructor asks a question is called “wait-time I.” Wait-time II is a 3 to 5-second time-frame of silence provided by the instructor after the learner gives a response that provides the learner time to think and extend their initial answer to the question if needed. Thus, wait-time provides the learner with “think-time.” The benefits of using wait-time are well documented in the educational literature (Rowe, 1986; Small, 1988; Sachdeva, 1996; Schneider et al., 2004; Nicholl & Tracey, 2007; Cho et al., 2012; Long, 2015; Barrett et al., 2017).9-16 Using wait-times I and II may appear to be challenging to utilize when teaching in busy patient care settings, but just taking the time to be silent for 3 to 5 seconds to give learners, especially the more introverted learners, a little more think-time can increase the quantity and quality of learners’ answers to questions. Overall, wait-time has been shown to enhance the teaching and learning process. Using wait-time can be applied to all four practice points of the ARCH model described in this paper. Remember, wait-time provides think-time.

Practice Points for Implementing the A of ARCH: Ask & Allow for Self-Assessment

Three practice points are important when implementing A of ARCH.

- Create a safe climate for the learner to give and receive information.

When arches were originally made of stone, the stone at the top center was called the keystone. If the keystone were removed, the arch would collapse because its integrity depended on it. Likewise, making the learner feel safe in verbalizing strengths and weaknesses are the keystone of the ARCH model.

- Ask and Allow the learner to self-assess an encounter with a patient while you observe.

An example question to learners after you have observed them interview and examine a child with the mother present might be: What is something specific you did well during the encounter when you obtained a history from Ms. Jones about her child’s ear-ache and then examined the child’s ears, and what is something on which you think you can improve? Avoid asking a broad question such as, “How do you think that went?” Suppose the teacher establishes a pattern of asking the learner to report on something specific that was done well and something specific needing improvement after a patient encounter. In that case, learners will get in the habit of self-assessing their particular actions in anticipation of the teacher’s question, and, importantly, it will make the conversation with the learner more time efficient.

- Use the learner’s self-assessments as a launching pad for discussion of the next components of the model (RCH).

Practice Points for Implementing the R of ARCH: Reinforce Learner for Things Being Done Well

Three practice points are suggested for effectively reinforcing what the learner is doing well.

- Recognize and reinforce the learner’s self-assessed strengths before adding strengths you, the teacher, identified.

- Explore how the learner worked to improve knowledge or skills and how the learner determined the improvement was satisfactory.

- Add skills you have directly observed the learner doing well that the learner did not mention.

Be specific and state why those good skills are essential. This will make learners’ tacit skills (e.g., making good eye contact with the patient) and knowledge more explicit to them and thus more likely to be repeated.

Practice Points for Implementing the C of ARCH: Confirm with the Learner What Needs Correction/Improvement

Three practice points are suggested to confirm the knowledge and skills the learner needs to improve or correct. Remember that in the A of ARCH, the teacher asked the question, “What is something you did well, and what is something you need to improve?” The three practice points are as follows.

- Clarify the learner’s self-identified area(s) for correction/improvement by verbalizing what they said and then checking for learner agreement.

- If needed, share something the learner needs to correct that the learner failed to mention that may be critically important to improve. Be descriptive, not judgmental.

- Avoid overwhelming the learners with too much to improve or correct.

Practice Points for Implementing the H of ARCH: Help Learner with an Improvement Plan

Four practice points are suggested to help learners with an improvement plan.

- Ask learners how they might correct or improve specific knowledge or skills and locate information related to those skills or knowledge.

- Add your thoughts/suggestions for improvement collaboratively.

- Have learners verbalize/summarize the specific improvement plans, and if needed, ask them to outline the plans in writing and share them with you.

- Make it clear to learners that you are available and willing to be a coach as needed and invite learners to ask you for help. Learners must view you as a “safe source” for help as needed.

Current Thoughts/Principles in Medical Education Supported by Using the ARCH Model

The ARCH model speaks to four important concepts in medical education: (1) learner self-assessment, (2) growth mindset, (3) master adaptative learner, and (4) practice-based learning and improvement. ARCH creates the environment for all four concepts/characteristics to flourish.

The ARCH model begins with a learner’s self-assessment (e.g., “What is something you did well, and what is something you can improve?”). Asking the student to self-assess and then making it safe for the learner to give an honest answer helps facilitate a growth mindset within the learner, which is an implicit belief by the learner that intelligence and abilities are changeable rather than fixed.17 Thus, a learner with a growth mindset looks for opportunities to continuously improve knowledge, skills, and attitudes. A learner’s feeling of safety when engaging in the improvement process fosters those opportunities. ARCH also facilitates the development of the “master adaptive learner” as the master adaptive learner routinely engages in four aspects of learning, those being: (1) Creates plans for improvement, (2) Engages in the improvement process, (3) Assesses the effectiveness of the improvement strategy, and (4) Makes adjustments as needed.18 All of these concepts/principles can take place in the context of clinical training that constitutes the important ACGME Competency Domain of Practice-Based Learning and Improvement.19

ARCH as A flexible Model

ARCH is a flexible model because it can be applied in several different learning settings. It can be used routinely in the context of precepting a student or resident in the office or hospital setting. It is a beneficial model for sitting with a learner and conducting a mid-clerkship feedback and guidance session. It can also be used to structure an end-of-week feedback and guidance discussion between the teacher and learner in which accomplishments and needed areas for improvement are documented with associated improvement strategies discussed. Likewise, ARCH can be utilized to guide an end-of-clerkship discussion in which the teacher and learner summarize what the student did well during the clerkship and what skills they may wish to improve in upcoming clerkships.

Closing Thoughts

Feedback and guidance via the ARCH Model is an engagement process in which the teacher engages the learner in a manner that helps the learner form the enduring habit of self-assessing, creating strategies for improvement, and implementing those strategies with coaching as needed. Any teaching strategy works better if the learner is aware of the teaching strategies employed by the teacher. For this reason, it is essential to introduce the ARCH model to the learner as part of an orientation at the beginning of a clerkship/rotation. Let the learner know about the components of ARCH and when and where you will employ the model as a regular part of the teaching process. This will enable the learner to anticipate your use of the ARCH components and to mentally prepare for the questions associated with the model. This will help ensure the success of both the teacher and the learner throughout a clerkship/rotation.

Attribution: The author would like to extend thanks to Roxann Mouratidis for her guidance in manuscript submission preparation and clarifying and formatting references.

Financial Disclosures: The author reports no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baker SD, Turner G, Bush SC. ARCH: a guidance model for providing feedback to learners. Education Column. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. 2015. https://www.stfm.org/publicationsresearch/publications/educationcolumns/2015/november/. Accessed April 20, 2022.

- Lama, A. The ARCH Guidance Model for providing effective feedback. MedEdPearls. 2023. https://harvardmacy.org/blog/january-2023-med-ed-pearls.

- Van de Ridder JMM, Wijnen-Meijer. Pendleton’s Rules: a mini-review of a feedback method. AJBSR. 2023;19(1):19-21.

- French JC, Colbert CY, Pien SC, et al. Targeted feedback in the milestones era: utilization of the Ask-Tell-Ask Feedback Model to promote reflection and self-assessment. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e274-e279.

- Sargeant J, Mann K, Manos S, et al. R2C2 in action: testing an evidence-based model to facilitate feedback and coaching in residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):165-170.

- Hall C, Peleva E, Vithlani RH, et al. FEEDBACK: a novel approach for providing feedback. Clin Teach. 2019;17(1):76-80.

- Fainstad T, McClintock AA, Van der Ridder MJ, Johnston SS, Patton KK. Feedback can be less stressful: medical trainees’ perceptions of using the Prepare to ADAPT (Ask-Discuss-Ask-Plan Together) Framework. Cureus. 2018;10(12):e3718.

- Quirk, M. Intuition and Metacognition in Medical Education: Keys to Developing Expertise. New York (NY): Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

- Rowe MB. Wait time: slowing down may be a way of speeding up! J Teach Educ. 1986;37(1):43-50.

- Small PA. Consequences for medical education of problem-solving in science and medicine. J Med Educ. 1988;63(11):848-853.

- Sachdeva AK. Use of effective questioning to enhance the cognitive abilities of students. J Cancer Educ. 1996;11(1):17-24.

- Schneider JR, Sherman HB, Prystowsky JB, Schindler N, DaRosa DA. Questioning skills: the effect of wait time on the accuracy of medical student responses to oral and written questions. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 Suppl):S28-S31.

- Nicholl HM, Tracey CA. Questioning: a tool in the nurse educator’s kit. Nurse Educ Pract. 2007;7(5):285-292.

- Cho YH, Lee SY, Jeong DW, et al. Analysis of questioning technique during classes in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:39.

- Long M, Blankenburg R, Butani L. Questioning as a teaching tool. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):406-408.

- Barrett M, Magas CP, Gruppen LD, Dedhia PH, Sandhu G. It’s worth the wait; optimizing questioning methods for effective intraoperative teaching. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87(7-8):541-546.

- Dweck CS. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House Publishing Group; 2006.

- Cutrer WB, Miller B, Pusic MV, et. al. Fostering the development of master adaptive learner: a conceptual model to guide skill acquisition in medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92(1):1-15.

- Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, Hamstra S, Holmboe ES. ACGME Milestones Guidebook. 2020. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf.