Lemierre Syndrome in an Adolescent: A Case Report

AUTHORS:

Carly Kinzer, BA1; Bliss Colao, BS1; Tristan Loveday, MD2; Mobeen H. Rathore, MD, FAAP1,3,4

1University of Florida College of Medicine

2Vanderbilt University Medical Center

3University of Florida Center for HIV/AIDS Research, Education and Service (UF CARES)

4Wolfson Children’s Hospital

CASE REPORT | PUBLISHED Winter 2026 | Volume 46, Issue 1

DOWNLOAD PDF

Abstract

Lemierre syndrome, a rare and life-threatening complication of pharyngitis, is characterized by bacteremia and septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. Typically caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum, this syndrome has become uncommon since the advent of antibiotics but has seen a rise in reported cases in recent decades. We present the case of a 14-year-old male with Lemierre syndrome, aiming to elucidate its clinical presentation, diagnostic nuances, treatment approaches, and outcomes in the adolescent population. The previously healthy adolescent presented with a history of fever, severe sore throat, and anorexia. Physical examination revealed dehydration, posterior oropharyngeal erythema, tender cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly. Blood cultures and Doppler ultrasound played a crucial role in confirming the ultimate diagnosis. The patient’s complex treatment course, involving antibacterial therapy, anticoagulation, and surgical intervention for osteomyelitis, highlights the multidisciplinary approach required in managing Lemierre syndrome. This case report contributes valuable insights into the nuances of Lemierre syndrome in adolescents, emphasizing the need for heightened clinical awareness, early recognition, and prompt intervention.

Background

Lemierre syndrome (LS), also known as postanginal sepsis or necrobacillosis, is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of pharyngitis characterized by bacteremia and septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein (IJV). It is typically caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum, a Gram-negative, obligate anaerobic rod that is part of the normal oral flora.1 However, other pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Eikenella corrodens, streptococcal species, and Klebsiella pneumoniae have also been implicated.2,3 LS usually affects immunocompetent young adults, with a higher prevalence in men.1,4 Its incidence is estimated at one case per million people annually, but is over ten times higher among teenagers and young adults in their early twenties.3,5 Although once more common before the widespread use of antibiotics, LS has reemerged since the late 1970s, likely due to decreased empiric antibiotic use for oropharyngeal and upper respiratory infections.³ Despite its rarity, the rising incidence and potential for severe morbidity in otherwise healthy young individuals make early recognition and treatment critical.⁶

We present the case of a 14-year-old male with LS.

Objective

To elucidate the clinical presentation, diagnostic nuances, treatment approaches, and outcomes of Lemierre syndrome in the adolescent population through the case of a 14-year-old male.

Subject Presentation

A previously healthy 14-year-old male with dental braces developed fever, severe sore throat, decreased appetite, and nausea and vomiting, which persisted for four days before he presented to the pediatric emergency department. He noted swollen neck lymph nodes, initially extending to his jaw but improving at the time of evaluation. One week prior, he had gone water tubing at a local state park.

On physical exam, he appeared dehydrated with posterior oropharyngeal erythema, tender cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly. Initial labs showed thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and elevated inflammatory markers (Table 1). Empiric antibiotics were started with IV ampicillin-sulbactam and oral doxycycline.

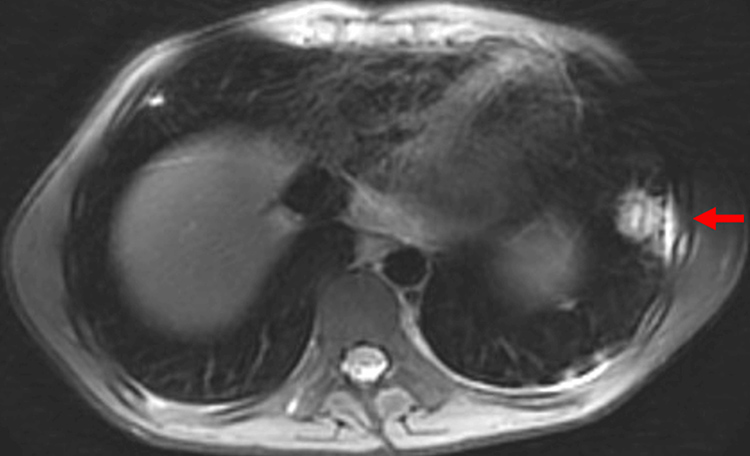

Table 1: Initial Notable Laboratory Values of the Patient

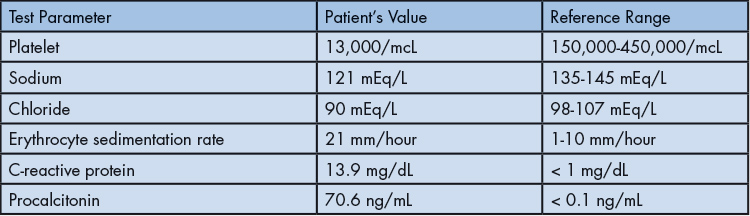

The differential diagnosis included bacterial and viral pharyngitis, acute mononucleosis, tick-borne illnesses (e.g., Ehrlichia, Rickettsia), Leptospirosis (given water exposure), and Lemierre syndrome (LS) secondary to Fusobacterium. Rapid Streptococcus pyogenes and Monospot® tests were negative, and throat culture later confirmed no Streptococcus pyogenes growth. Blood cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) were drawn. Doppler ultrasound revealed a nonocclusive right internal jugular vein (IJV) thrombus (Figure 1). Anaerobic blood cultures grew Gram-negative bacilli within 24 hours. Abdominal ultrasound showed mild hepatosplenomegaly and a minor left pleural effusion without inferior vena cava thrombus. Antibiotics were escalated to IV meropenem, and anticoagulation was initiated.

Figure 1: Neck ultrasound with Doppler in long axis view showing nonocclusive right internal jugular vein thrombus.

During hospitalization, the patient remained febrile, tachycardic, and tachypneic in the early course but gradually improved. He developed left upper quadrant abdominal and costal tenderness. Anticoagulation was briefly paused due to severe thrombocytopenia (platelets 13,000/mcL) but resumed once platelets recovered to 86,000/mcL.

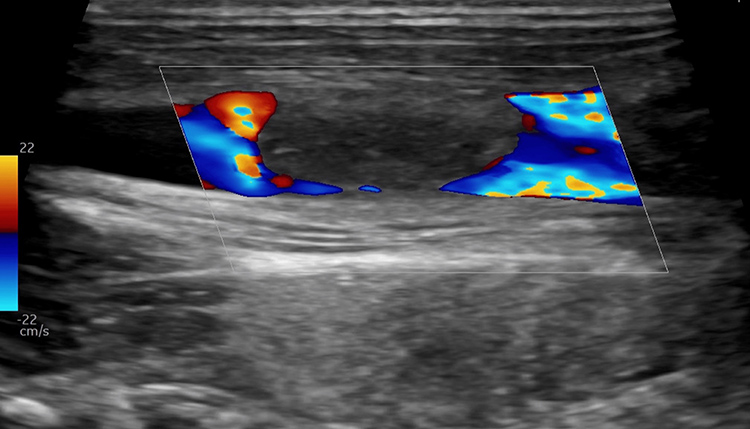

Subsequently, the patient developed bilateral foot edema, which progressed to the entire left lower extremity, associated with weight-bearing pain and tenderness over the medial posterior left knee. Doppler ultrasound ruled out deep vein thrombosis. MRI revealed distal left femoral osteomyelitis with a subperiosteal abscess (Figure 2). He underwent surgical joint washout and drainage.

Figure 2: Magnetic resonance showing distal left femoral osteomyelitis with subperiosteal abscess (red arrow).

Postoperatively, persistent left upper quadrant pain and new warmth and swelling over the left lower ribs were noted. Chest MRI revealed osteomyelitis of the left seventh rib, a subperiosteal abscess, a pleural abscess, and multiple lung nodules suggestive of septic emboli (Figure 3). Antibiotic therapy was transitioned to continuous IV piperacillin-tazobactam.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance showing osteomyelitis of the left seventh rib with subperiosteal abscess (red arrow), pleural abscess, and multiple lung nodules concerning for septic emboli.

Repeat Doppler studies showed enlargement of the right IJV thrombus. The patient was discharged on oral rivaroxaban and IV piperacillin-tazobactam via PICC line and completed a six-week course of IV antibiotics.

Discussion

LS usually results from a pharyngeal infection but has also been reported following dental work or mastoiditis.2,3 The bacteria use the lymphatic system to invade the lateral pharyngeal space, reaching the IJV.3,4 Common symptoms include prolonged sore throat, high fever, neck pain, dysphagia, swelling of the sternocleidomastoid, and cranial nerve palsies.2,4 Once the IJV is infected, septic emboli can seed other areas of the body, causing septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, pyomyositis, pneumonia, renal and liver involvement, endocarditis, and sepsis.3,4 Rarely, CNS involvement can also occur.7

While the diagnosis is primarily clinical, a CT scan of the neck is the best imaging modality for diagnosing thrombosis of the IJV.4,7,8 Doppler ultrasound can also aid in diagnosis but is less sensitive.7,8 Blood cultures should be performed to identify the causative organism. The mainstay of treatment involves supportive care and IV antibiotics, typically three to six weeks in duration. Depending on the severity of clinical illness, empiric antibiotic therapy should be effective against anaerobes, including F. necrophorum, as well as Gram-positive infections caused by Staphylococcus and streptococci, and Gram-negative organisms. Antibiotic therapy may include penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, clindamycin, carbapenems, or metronidazole.1,2,4 F. necrophorum is resistant to fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, and macrolides.4 Antibiotics should be tailored based on culture results and susceptibilities. Surgical intervention, such as incision and drainage or vein excision, should be routinely considered, as literature supports its role alongside antibiotics and supportive care as core components of treatment.1,4

In our case, we transitioned from meropenem to continuous intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam to maintain broad-spectrum and anaerobic coverage while supporting antibiotic stewardship by minimizing carbapenem use. Additional considerations included adequate bone penetration and alignment with the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for polymicrobial infections.9 Continuous infusion of piperacillin-tazobactam was also selected to optimize pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic targets, maintaining consistent drug levels and potentially improving clinical outcomes in critically ill patients.10,11

Due to the formation of blood clots in LS, anticoagulation is initiated in over 60% of patients, though its use is controversial.2 Options include heparin, low molecular weight heparins, warfarin, or direct oral anticoagulants.2 A 2020 meta-analysis found a decreased incidence of new venous thromboembolism or septic lesions in patients on anticoagulation.12 However, a different meta-analysis found no statistically significant difference in mortality between patients with LS who received anticoagulation and those who did not.2 The decision to implement anticoagulation in this case was guided by the patient’s clinical progression and thrombus development.

This case report contributes to the existing literature by highlighting the complex presentation and progression of LS in an adolescent patient. Our patient exhibited a constellation of symptoms, including severe sore throat, fever, and lymphadenopathy, prompting consideration of various differential diagnoses, such as bacterial and viral etiologies. Their clinical course, marked by persistent fevers and thrombocytopenia, exemplifies the complexities associated with LS. The case also reveals classic complications of LS, including the development of osteomyelitis at multiple sites.

The rarity of LS demands a high index of suspicion and presents significant diagnostic challenges, often mimicking more common causes of pharyngitis. Clinicians should maintain a strong clinical suspicion in cases of acute tonsillopharyngitis accompanied by persistent neck pain and signs of sepsis. Accurate diagnosis in our case relied on a multidisciplinary approach and was ultimately confirmed through Doppler ultrasound, CT imaging, and blood cultures, identifying Fusobacterium necrophorum. The decision to initiate anticoagulation highlights the complexities of individualized treatment plans. While this case supports existing knowledge of LS, the unique aspects observed emphasize the need for continued research and additional case reports to refine diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Financial Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rathore MH, Barton LL, Dunkle LM. The spectrum of fusobacterial infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:505-8.

- Gore MR. Lemierre Syndrome: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;24:379-385.

- Allen BW, Anjum F, Bentley TP. Lemierre Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023.

- Lee WS, Jean SS, Chen FL, Hsieh SM, Hsueh, PR. Lemierre’s syndrome: a forgotten and re-emerging infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:513-17.

- Kristensen HL, Prag J. Lemierre’s syndrome and other disseminated Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in Denmark: a prospective epidemiological and clinical survey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:779-89.

- Nygren D, Holm K. Invasive infections with Fusobacterium necrophorum including Lemierre’s syndrome: an 8-year Swedish nationwide retrospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1089.

- Kuppalli K, Livorsi D, Talati NJ, Osborn M. Lemierre’s syndrome due to fusobacterium necrophorum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:808-15.

- Tiwari A. Lemierre’s syndrome in the 21st century: a literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:43685.

- Thabit AK, Fatani DF, Bamakhrama MS, et al. Antibiotic penetration into bone and joints: An updated review. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;1:128-136.

- Klastrup V, Thorsted A, Storgaard M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of piperacillin following continuous infusion in critically ill patients and impact of renal function on target attainment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(7):e02556-19.

- Yang H, Zhang C, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Chen L. Clinical outcomes with alternative dosing strategies for piperacillin/tazobactam: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0116769.

- Valerio L, Zane F, Sacco C, et al. Patients with Lemierre syndrome have a high risk of new thromboembolic complications and clinical sequelae. and death: an analysis of 712 cases. J Intern Med. 2021;289:325-39.