Foreign Body Sensation in a Contact Lens Wearer

AUTHORS:

Malcolm M Kates, MD1,2; Carolyn G. Carter, MD, MS3

1College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

2Transitional Year Residency Program, Brookwood Baptist Health, Birmingham, AL

3Division of General Pediatrics, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL

Case Report | PUBLISHED WINTER 2023 | Volume 43, Issue 1

DOWNLOAD PDF

CASE PRESENTATION

An 18-year-old girl presented to an outpatient pediatric clinic concerned about a new “white spot” in her left eye causing pain and increased tearing. She developed symptoms the previous evening and attributed them to exposure to a new air freshener and drying of her contact lens. Her symptoms did not improve with removal of the contact lens or saline eye drops. Her vision was unimpaired and she described a foreign body sensation. She denied any trauma to the region. Her medical history was significant for atopy (including allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, asthma, and shellfish/peanut allergies), herpes simplex infection, depression, anxiety, and myopic astigmatism for which she wore glasses and contacts interchangeably.

On physical examination, the patient appeared well-developed, alert, and in no acute distress. Vital signs were all within normal limits for age. Ophthalmic examination revealed injection of the left bulbar conjunctiva, clear non-mucoid drainage from the left eye, and a 1 mm circular white lesion in the medial upper quadrant of the iris (Figure 1). The skin surrounding the patient’s eye was devoid of rashes, but mild periorbital erythema was noted along lid margins. She had full, non-painful range of extraocular motion in the affected eye. A saline rinse was unable to remove the lesion in clinic. Intraocular pressure in the affected eye was unremarkable at 13 mmHg (normal range 12-22 mmHg). Visual fields were intact throughout and visual acuity via Snellen eye chart was 20/30 in the affected eye which was consistent with the patient’s baseline.

Figure 1. Circular white lesion in the superior nasal quadrant of the left eye.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Although perceived by the patient to be a foreign body, the lesion was identified as a corneal ulcer.

DISEASE COURSE

As the saline rinse was not able to remove the presumed foreign body and it appeared likely the patient had a corneal ulcer, the patient was referred the same day to an ophthalmologist where a wound sample was obtained for culture on Chocolate, Sabauraud, and Blood agar plates alongside gram stain and cytology. The patient was started on empiric ophthalmic moxifloxacin drops hourly while awake and every four hours when sleeping along with routine warm compresses and lid scrubs. At Day 5 of follow-up, the patient returned to the ophthalmology clinic with a persistent, though unchanged, lesion. Cultures showed no growth and gram stain revealed no organisms. She was asked to continue the aforementioned moxifloxacin regimen and return to clinic in one week. At Day 12 follow-up, a small scar was seen overlying the region of the initial lesion with total resolution of symptoms and no change in visual acuity.

DISCUSSION

Much like the adult population, complaints related to the eyes and visual system among pediatric and adolescent patients account for roughly 3-5% of all outpatient physician visits.1,2 A variety of conditions can cause the combination seen here of eye pain, conjunctival injection, and foreign body sensation. These include traumatic causes (e.g., corneal abrasion, chemical or other exposure, ocular foreign body), infectious causes (e.g., corneal ulcer, conjunctivitis, herpes simplex keratoconjunctivitis, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, infectious keratitis), and others (e.g., acute angle-closure glaucoma, autoimmune uveitis/iritis). Of note, though often used interchangeably, keratitis and corneal ulcer are not direct equivalents. Keratitis, which is often bacterial in nature, refers to inflammation of the cornea whereas a corneal ulcer refers to loss of corneal tissue, which may occur alongside a bacterial infection, but does not necessarily do so. Corneal ulcers may be a sign of varying underlying conditions including both keratitis and iritis.3

Diagnosis of a corneal ulcer is largely clinical in nature. The examination begins with a careful consideration of patient risk factors and presenting concerns. A history of contact lens use, ocular surgery, trauma, or prior herpes infection combined with presenting complaints of pain, rapid onset, photophobia, tearing, or vision changes necessitate concern for a corneal ulcer. Contact lens users are at increased risk for corneal ulcers, particularly those who sleep in them which increases the risk of corneal ulcers 9-15 times that of the general population.4

As seen here, it is not uncommon for patients to describe a painful foreign body sensation when blinking.5 Initial examination should consist of the eye “vital signs” including acuity, pupillary dilation, reactivity, and intraocular pressure. Further evaluation may reveal injection, ciliary flush, or hypopyon. Staining with fluorescein can also help visualize an epithelial defect such as a corneal ulcer. While primary care providers may reasonably treat and monitor small corneal abrasions, the risk of vision loss with corneal ulcers is high, such that urgent or emergent ophthalmologic referral and evaluation is indicated.6,7

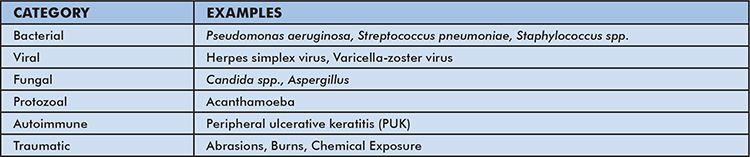

The clinical appearance of an ulcer is often unreliable in determining the causative agent thus further diagnostic studies, including culture and sensitivity testing, is recommended. The most common etiology is bacterial in nature with Pseudomonas aeruginosa being the most common pathogen among contact lens wearers.8 Empiric monotherapy with a fluoroquinolone such as moxifloxacin is often first-line with subsequent tailoring based on sensitivity profiles.9 However, corneal ulcers can also occur from viral (particularly herpes simplex virus type-1), fungal, protozoal, or autoimmune etiologies (Table 1). Among contact lens users, particularly those with corneal ulcers not responding to antibiotics, concern should be given to possible acanthamoeba infection as this can be very serious and is exclusively seen in contact lens wearers.10

Prognosis is largely based on the initial characteristics of the corneal ulcer (size, etiology), and response to treatment. If improperly treated or left untreated, complications can include perforation, corneal scarring, endophthalmitis (spread of the infection into the eye), and vision loss. Scarring, as seen in this patient, may be minor or cause visual changes depending on the location and severity of the ulcer.

Table 1: Differential Diagnosis of Tinea Faciei

CONCLUSION

Disorders of the visual system are common in the outpatient pediatric and adolescent population. Contact lens use is associated with an increased risk for multiple ophthalmic conditions including corneal ulcers. Appropriate work-up for patients with conjunctival injection, pain, and foreign body sensation includes a thorough history and testing for visual acuity, pupillary dilation, reactivity, and intraocular pressure. If a corneal ulcer is suspected, urgent or emergent referral to an ophthalmologist for swab and culture is indicated to help guide antibiotic therapy. Empiric treatment with a topical fluoroquinolone should be started, typically by an ophthalmologist, and therapy should be adjusted based on culture results. Patients should be carefully followed to ensure adequate response to treatment and resolution.

REFERENCES

- Ku M, Lue K, Sun H. Major health-care providers and the 10 leading reasons for adolescent ambulatory visits. Pediatr Int. 2012;54(5):657-662.

- Teleki SS, Sorbero MES, Hilborne L, et al. Performance measurement in the hospital outpatient setting. RAND Health Working Paper. Dec 2007.

- Cronau H, Kankanala RR, Mauger T. (2010). Diagnosis and management of red eye in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2): 137-144.

- Schein OD, Poggio EC. Ulcerative keratitis in contact lens wearers: incidence and risk factors. Cornea. 1990;9 Suppl 1:S55-8; discussion S62-3.

- Weiner, G. (2012). Confronting corneal ulcers – Pinpointing etiology is crucial for treatment decision making. EyeNet Magazine.

- Farahani, M., Patel, R., Dwarakanathan, S. Infectious corneal ulcers. Disease-a-month: DM 2017;63(2): 33.

- Garg P, Rao GN. Corneal ulcer: diagnosis and management. Community eye health. 1999;12(30): 21.

- Weisenthal R, Afshari N, Bouchard C, et al. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC), 2014–2015: Section 8: External Disease and Cornea, American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco (2015).

- Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11): 1678-1689.

- Bennett L, Y Hsu H, Tai S, et al. Contact lens versus non-contact lens-related corneal ulcers at an academic center. Eye Contact Lens. 2019;45(5):301-305.