Testicular Point-of-Care Ultrasound Utilization for Pediatric Patients

AUTHORS:

Paul Khalil, MD1,2,3; Ee Tay, MD4; Antonio Riera, MD5; Samuel Lam, MD6; Adam Sivitz, MD7

1University of Louisville School of Medicine; 2Norton Children’s Hospital; 3Nicklaus Children’s Hospital

4Hassenfield Children’s Hospital an NYU Langone;

5Yale University

6Children’s Colorado

7Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

ORIGINAL RESEARCH | PUBLISHED Winter 2026 | Volume 46, Issue 1

DOWNLOAD PDF

Abstract

Background

Acute scrotal pain is a common presentation to the Pediatric Emergency Department. Testicular point-of-care ultrasound studies performed in the Emergency Department may assist in expediting diagnosis and management. Access to point-of-care ultrasound or radiology ultrasound for acute scrotal pain may vary by institution.

Objectives

This study aims to be a descriptive study with regard to the utilization of ultrasound and access to surgical management for pediatric patients who present with acute scrotal pain in the Pediatric Emergency Department.

Methods

A survey inquiring about hospital settings, institutional types, availability of point-of-care ultrasound, radiology ultrasound, and surgical management for scrotal pathology and testicular was sent to two different Listervs. A second survey to further evaluate ultrasound use for testicular torsion management was sent to institutions that perform scrotal point-of-care ultrasound.

Results

The initial survey had 314 respondents from 147 separate institutions. Most respondents worked in an urban, academic, or Pediatric Emergency Department setting. Fourteen percent of the respondents perform a point-of-care ultrasound prior to radiology ultrasound for testicular torsion. Still, if the point-of-care ultrasound is negative for findings, 84% will order a radiology ultrasound study for further evaluation. For those institutions with surgical management capability, only 3% of the surgeons would operate on testicular torsion based on positive point-of-care ultrasound findings.

Conclusion

Performance of testicular ultrasound by point-of-care ultrasound remains low despite the urgency of rapid treatment for testicular torsion, as the salvage rate drops to 20-50% if operating room management is delayed 6 to 12 hours. Opportunities to encourage point-of-care ultrasound use for scrotal pathology may expedite management when compared to radiology ultrasound. Further study is needed to inquire into behavior and barriers preventing more point-of-care ultrasound use in the Pediatric Emergency Department.

Introduction

Acute scrotal pain is a common presentation to the Emergency Department (ED), making up approximately 0.5% of visits.1,2 The severity of the diagnosis ranges from minor (epididymitis or torsion of the testicular appendage) to fertility-threatening conditions (testicular torsion). History and physical exam alone cannot be relied upon, as these conditions can mimic each other.1,3,4 One case series of acute scrotal presentations described testicular torsion as the final diagnosis in 10% of the cases.5

Historically, a physical exam, urinalysis, and a radioisotope scan were used to differentiate between benign and surgical conditions.1 However, ultrasound has now become the gold standard in the evaluation of scrotal pain.3,6

Testicular torsion is the most time-sensitive diagnosis to make in a patient with an acute scrotum presentation.7,8 Frohlich et al showed that testicular salvage was around 90-100% if managed in the operating room within the first 6 hours of symptoms. Salvage drops to 20-50% if operating room management is delayed to 6 to 12 hours, and 11% if delayed beyond 12 hours.7 This is particularly concerning, as at a Canadian academic center, Chan et al found that most patients presented to the ED at 4 hours after the onset of testicular symptoms and were not evaluated for an average of 79.8 minutes after presentation. An additional 48 minutes elapsed if an ultrasound was performed.9 Overholt showed that in a rural setting, where patients need to be transferred for ultrasound, there was an additional 6 hours of delay before surgery (12.9 hours from onset of symptoms compared to 6.9 hours to those not needing transfer).10

Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) is a modality that can be readily performed at the bedside by a physician trained in its use. Friedman et al found in a retrospective study that performing POCUS saved 73 minutes in time to diagnosis when compared to radiology ultrasound (RADUS) in their evaluation of scrotal pain. Their POCUS studies demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 99% specificity when compared to RADUS ultrasound results.11

This study aims to describe the utilization of ultrasound and access to surgical management for pediatric patients who present with acute scrotal pain in the Pediatric ED.

Materials & Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Participants:

The survey was distributed to the members of P2Network and the Brown Pediatric Emergency Room (PEM) Listserv. The P2Network (The P2 standing for “PEM POCUS”) is an international organization comprised of PEM POCUS communities with 375 members. The Brown PEM listserv includes approximately 2800 providers throughout the world with interests in PEM topics. All of our surveys were voluntary, and participants consented to the study when completing the survey.

Study Design:

The survey was designed by three PEM POCUS leaders, discussed during two online meetings, and edited by an additional eight PEM POCUS leaders.

First Iteration:

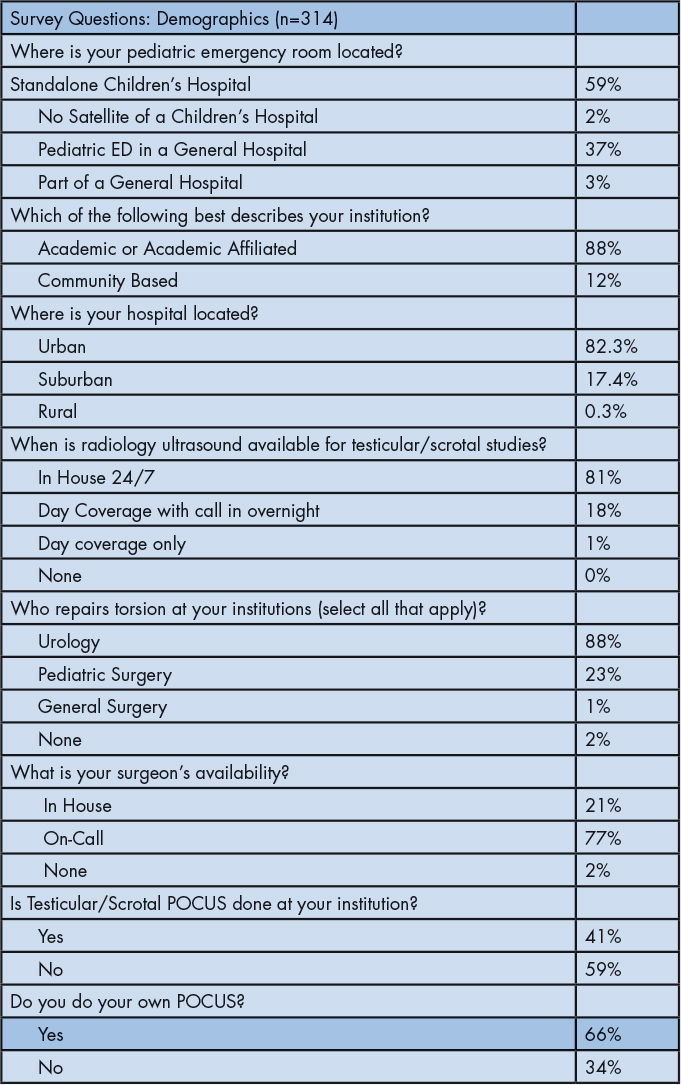

The first survey was sent to all P2Network and Brown listserv members. Disclosure of home institution was not required for participants. Demographic questions were based on the location where providers worked most of their shifts (Table 1). Questions included the availability of scrotal ultrasounds and consultants for the management of scrotal pathology in the ED. If providers indicate that they do testicular POCUS, they may continue to the next section of the survey (Table 2). If the provider cannot perform testicular POCUS in the ED, they do not continue to the following section.

Table 1: Demographics of intuitions who completed the survey.

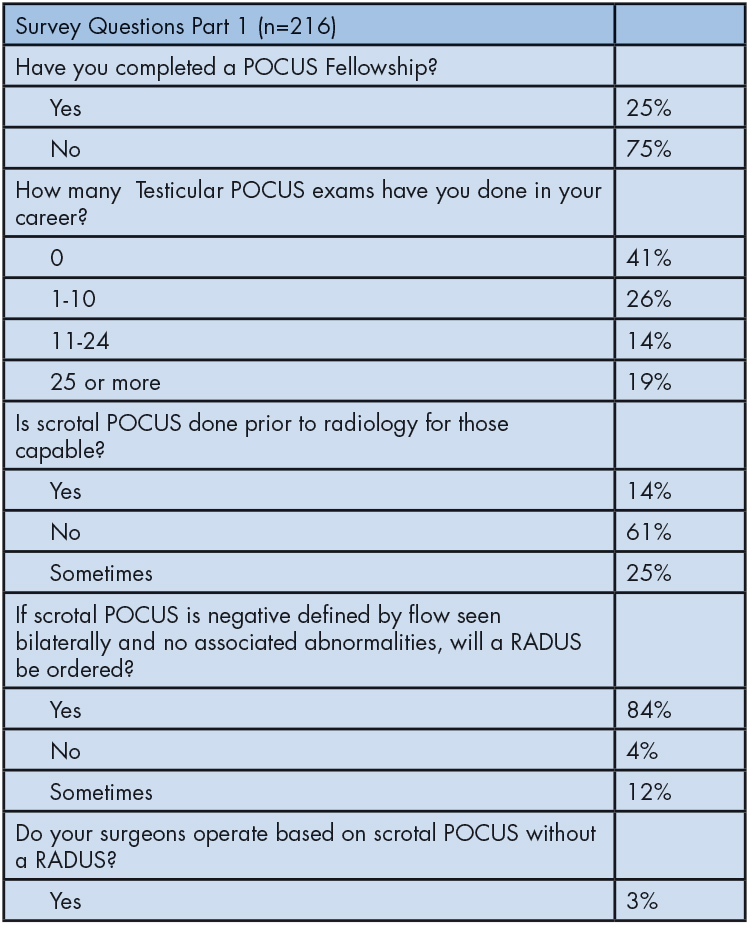

Table 2: Providers who do POCUS studies.

Second Iteration:

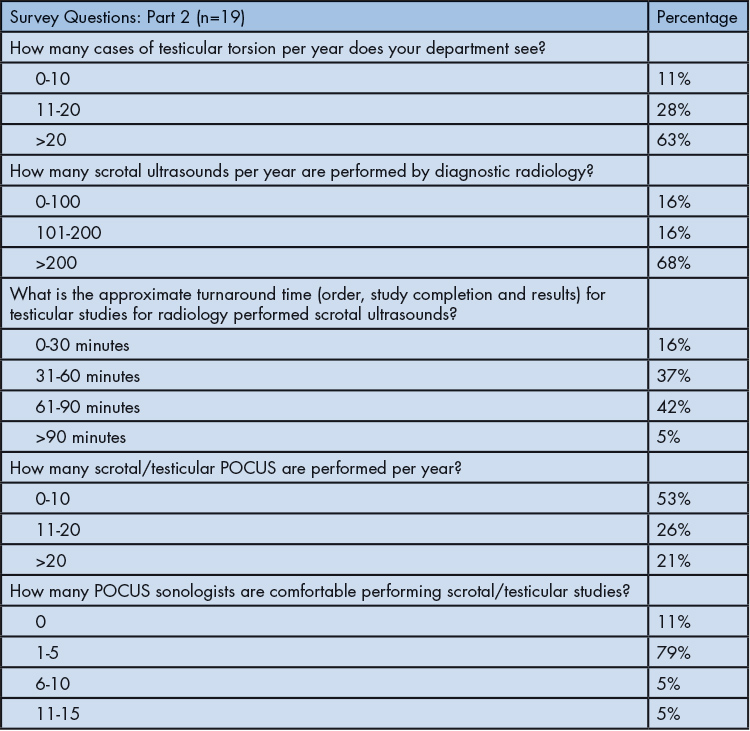

The second survey was sent by email to POCUS Directors. If there was no POCUS Director, it was sent to the Division Director at the institutions, who confirmed that testicular/scrotal POCUS is performed at their institutions. This five-question survey was designed to gain a better understanding of locations where testicular POCUS is performed (Table 3).

Table 3: Director’s responses at institutions where testicular POCUS is done.

Data Collection and Analysis Method:

REDCap (v11.1.16), an online, secure survey manager, was used to distribute the survey and collect responses.

Results

A total of 62 completed the first survey from 147 separate institutions, with a response rate of 10%. Most respondents work in an urban, academic, pediatric ED setting. In-house, 24-hour radiology ultrasound for testicular/scrotal ultrasound studies was available for 81% of the institutions. A large majority (98%) of these institutions have either urologists or general surgeons who manage testicular emergencies available on-call.

Only 41% of the respondents reported testicular or scrotal POCUS being performed at their institutions. Approximately 25% of the respondents completed a POCUS fellowship. However, almost 66% reported performing their own POCUS. Only 13% of PEM departments included testicular/scrotal ultrasound as part of their POCUS credentialing. Furthermore, only 14% reported testicular/scrotal POCUS routinely being performed before radiology studies in institutions capable of performing POCUS. In case of negative testicular/scrotal POCUS, 84% of respondents would proceed to order a confirmatory ultrasound in radiology. Only 17% of institutional surgeons would consider operating based on positive testicular/ scrotal POCUS alone. Similarly, only 18% of responding institutions reported their surgeons allowing testicular detorsion based on POCUS only. The top diagnoses made by testicular/ scrotal POCUS included testicular torsion (36%), hydrocele (26%), mass (17%), hernia (17%), and epididymitis (17%). A detailed breakdown of the responses is shown in Table 1.

A total of 62 institutions indicated they do testicular POCUS on the first survey, thus making them eligible for the second survey. Contact information for only 47 program directors was found (either POCUS Director or Division Chiefs), with 19 departments completing the follow-up survey describing current trends and practices related to ultrasound evaluation of the acute scrotum in their departments. Most departments reported that they care for more than 20 cases of testicular torsion (63%) annually, and RADUS performed more than 200 scrotal ultrasounds per year (68%) on average over the last 5 years. The process to complete RADUS with interpretation is usually between 31 and 90 minutes (79%), although three sites reported a turnaround time of under 30 minutes. One site reported a turnaround time greater than 90 minutes.

Compared to RADUS, the overall use of POCUS to evaluate the acute scrotum was much less frequent, with most programs reporting 0-10 bedside scans (53%) performed annually. Most programs reported having 1-5 PEM physicians (79%) in their group who felt comfortable performing scrotal/testicular POCUS. Full details of the survey results can be found in Table 3.

Discussion

Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) is a limited ultrasound at the bedside to answer a specific clinical question. Medical ultrasound was first developed in the 1950’s, with the first commercially used ultrasounds appearing in the 1960’s. Ultrasound was initially used by cardiology, radiology, and obstetrics/gynecology. In the late 1980’s, it was introduced to EM. Early EM POCUS focused on life-saving applications, looking for cardiac effusions and free fluid in trauma.

Formal training for EM POCUS began with minicourses in the early 1990’s and has since developed into a core competency for EM residents by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in 2001.12

The use of POCUS in Pediatric Emergency Medicine was first endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2015. A 2020 survey found 97% of PEM Fellowship programs incorporate POCUS in their education. POCUS has expanded from the early critical care applications to include looking for less acute pathology, such as in the lung (pneumonia) and soft tissue evaluations (abscess or foreign bodies).13

Testicular torsion is a time-sensitive diagnosis, as testicular viability decreases over time. POCUS can help accurately speed up diagnosis.11 This survey showed that many PEM providers are not comfortable with POCUS findings, and even when the PEM provider is comfortable, their surgical consultants tend not rely on these findings. This is consistent with prior surveys that concluded scrotal/testicular POCUS is viewed as an advanced modality.

PEM POCUS experts from the P2Network disagreed that testicular POCUS should be part of the PEM Fellowship or PEM POCUS Fellowship training. They conducted two Delphi-based survey studies, which required 80% consensus for approval to be included in the respective fellowships; 49% thought that scrotal POCUS should be part of fellowship training in Pediatric Emergency Medicine (PEM), and 79% felt it should be part of PEM POCUS Fellowship training, just short of the 80% requirement.14,15

This two-part survey regarding testicular/scrotal evaluation assessed throughput for children in the ED and the application of POCUS. The first part of the first survey was open to providers subscribing to the Listservs, and the second part was limited to those who do their own POCUS. Of the 314 providers who filled out the first survey, 65% stated that they do their own POCUS. This disparity can be noted as departments had 59% of the faculty credentialed in POCUS.

Our survey continued for those who indicated that they do POCUS with questions that touched on how often they do testicular/scrotal POCUS and if they use it for clinical decision-making. In an article published by Abo et al concerning credentialing PEM POCUS faculty, they recommended 25 scans to be credentialed in testicular/scrotal POCUS.16 In this survey, of those who performed POCUS, only 19% of providers had met the 25 testicular/scrotal scans milestone. Our survey also indicated that only 14% of those who perform POCUS do a testicular/scrotal POCUS before a RADUS routinely. Performing POCUS alone could save time and subsequent testicular viability. Friedman showed that a POCUS study saved 73 minutes in diagnosis at their institution. This 73-minute period could be the divergence between salvaging a testicle and its demise.11

One reason testicular/scrotal POCUS might not be performed is that providers do not think it is time-efficient. In the survey, only 3% of general surgeons and urologists routinely take testicular torsion to the operating room, based on a POCUS study alone. EM providers might be more willing to invest their time to learn and perform these POCUS studies if surgeons would rely on them. As previously noted, Friedman showed that POCUS by PEM physicians was 100% sensitive and 96% specific for the diagnosis of torsion.11 Stringer demonstrated that residents were able to achieve 96% accuracy with the video module-based education plus one hour of hands-on training. Twelve Emergency Medicine residents and 12 Urology residents were tested on their knowledge of scrotal ultrasound, and 96% were deemed competent after this training and maintained their expertise at a 3-month reassessment.17 This implies that there could be a role for POCUS in both high and low-probability settings, used in combination with a scoring system such as the Testicular Workup for Ischemia and Suspected Torsion (TWIST) score.18

Another reason there might be hesitation to perform these studies is fear of the consequences of missing a torsion, as well as the liability of missing the diagnosis.19,20 In this survey, emergency providers still order a RADUS in 84% of cases. where there is flow seen bilaterally, and there are no associated symptoms.

The second survey was distributed to POCUS program directors at sites where testicular/scrotal POCUS is performed. The director was requested to do research by contacting radiology, surgery, and electronic medical record personnel to get specific numbers. These sites, for the most part, saw large volumes and had significant pathology, with most seeing greater than 20 cases of torsion per year (63%). They were consistent with the Friedman study, with the highest number of sites (42%) taking 61-90 minutes with RADUS. Most institutions performed 10 or fewer POCUS studies per year (53%) compared to RADUS, which performed 201 (68%). Most of these studies are being conducted by 1-5 providers (79%).

Limitations:

This study had several limitations. Most providers who filled out this survey were based out of academic institutions, and most perform their own POCUS. This indicated a bias to those who are interested and invested in POCUS. Since the survey was sent out to PEM and POCUS listservs, several institutions responded more than once. This could indicate that those groups with more interest in POCUS are more likely to respond.

Another limitation is that in the first part of the survey, providers were given best-guess answers, thus allowing for recall bias.

In the second part of the study, directors were asked to consult with radiology to obtain more concrete answers. This, in part, could have led to the low response rate, particularly in the second half of the survey.

Conclusions:

Performance of testicular ultrasound by POCUS remains low despite how time-sensitive it is to diagnose testicular torsion. Even among those who do their own POCUS, they often order a confirmation RADUS study, and surgeons rarely take patients to the operating room based on POCUS. Opportunities to encourage POCUS use for scrotal pathology may expedite management when compared to RADUS. Further study is needed to inquire into behavior and barriers preventing more POCUS studies from being performed in the Pediatric ED.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the P2Network, Peter Snelling, Adriana Yock, Rosemary Thomas-Mohtat, Kelly Bergmann, Matthew Moake, Kristen Weerdenburg-Yeh, Kathryn Pade, and Michael Gottlieb for their assistance with this study.

Financial Disclosures:The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lewis AG, Bukowski TP, Jarvis PD, et al. Evaluation of acute scrotum in the emergency department. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30(2):P277–82.

- Thomas SZ, Diaz, VI, Rosario, J, et al. Emergency department approach to testicular torsion: Two illustrative cases. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4958.

- Lemini R, Guanà R, Tommasoni N, et al. Predictivity of clinical findings and Doppler ultrasound in pediatric acute scrotum. Urol J. 2016;13(4):2761–65.

- Molokwu CN, Somani BK, & Goodman CM. Outcomes of scrotal exploration for acute scrotal pain suspicious of testicular torsion: A consecutive case series of 173 patients. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):990–3.

- Lian T, Metcalfe P, Sevcik W, et al. Retrospective review of diagnosis and treatment in children presenting to the pediatric department with acute scrotum. Am J Roentgen. 2013;200(5):1001–5.

- Waldert M, Klatte T, Schmidbauer J, et al. Color Doppler sonography reliably identifies testicular torsion in boys. Urology. 2010;75(5):1170–74.

- Frohlich LC, Paydar-Darian N, Cilento BG,Jr, et al. Prospective validation of clinical score for males presenting with an acute scrotum. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(12):1474–1482.

- Visser AJ, Heyns, CF. Testicular function after torsion of the spermatic cord. BJU Int. 2003;92(3):200–3.

- Chan EP, Wang PZT, Myslik F, et al. Identifying systems delays in assessment, diagnosis, and operative management for testicular torsion in a single-payer health-care system. J Pediatr Urol. 2019;15(4):350e1–e6.

- Overholt T, Jessop M, Barnard J, et al. Pediatric testicular torsion: Does patient transfer affect time to intervention or surgical outcomes at a rural tertiary care center? BMC Urol. 2019;19:82.

- Friedman N, Pancer Z, Savic R, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound by pediatric emergency physicians for testicular torsion. J Pediatc Urol. 2019;15(6):608e1–e6.

- von Kuenssberg-Jehle D, Wilson C. Some recollections of early work with bedside ultrasound in emergency medicine: the first 10 years. J Am Coll Emerg Phys Open. 2020;1(5):871-5.

- Cramer N, Cantwell L, Ong H, et al. Pediatric emergency medicine fellowship point-of-care ultrasound training in 2020. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(4):e10643.

- Shefrin AE, Warkentine F, Constantine E, et al. Consensus core point-of-care ultrasound applications for pediatric emergency medicine training. AEM Ed Train. 2019;3(3):251–8.

- Constantine E, Levine M, Abo A, et al. Core content for pediatric emergency medicine ultrasound fellowship training: A modified Delphi consensus study. AEM Ed Train. 2019;3(3):244–50.

- Abo AM, Alade KH, Rempell RG, et al. Credentialing pediatric emergency medicine faculty in point-of-care ultrasound: Expert guidelines. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(1):49–54.

- Stringer L, Cocco S, Jiang A, et al. Point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of testicular torsion: A practical resident curriculum. Can J Surg. 2021;64(1):E47–53.

- Barbosa JA, Tiseo BC, Barayan GA, et al. Development and initial validation of a scoring system to diagnose testicular torsion in children. J Urol. 2013;189(5):1859–64.

- Bass JB, Couperus KS, Pfaff JL, et al. A pair of testicular torsion medicolegal cases with caveats: The ball’s in your court. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med, 2018;2(4):329–332.

- Gaither TW, Copp HL. State appellant cases for testicular torsion: Case review from 1985 to 2015. J Pediatr Urol, 2016;12(3):138.e1–e5.